P: (08)9965 0697 F: (08)9964 7528

News

Is psychosocial risk prevention possible? Nov 18th, 2014

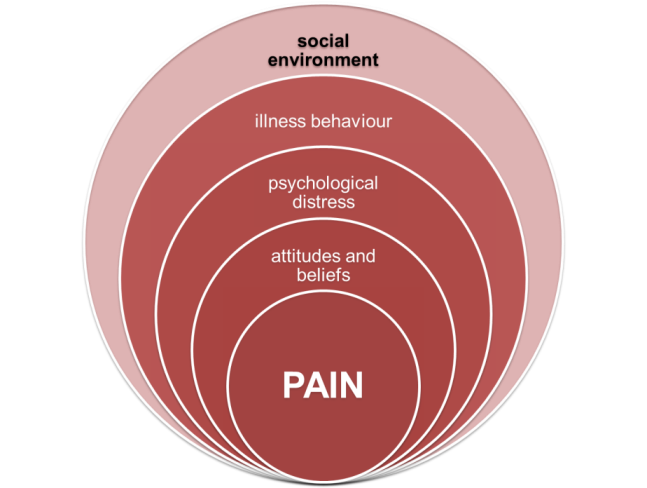

The following paper explores why this is still the case by discussing three presumptions in relation to the current state of evidence in this area.

Presumption 1: there is no clear definition and understanding of psychosocial risks by key stakeholders and businesses.

Psychosocial hazards are aspects of work organization, design and management that have the potential to cause harm on individual health and safety as well as other adverse organizational outcomes such as sickness absence, reduced productivity or human error. They include several issues such as work demands, the availability of organizational support, rewards, and interpersonal relationships, including issues such as harassment and bullying in the workplace. The types of issues employers are asked to consider include workload, work schedules, role clarity, communication, rewards, teamwork, problem-solving, and relationships at work.

Can any business flourish without effectively managing these issues? And if there is clear evidence that not managing these issues effectively can lead to poor employee health, presenteeism, absenteeism, human error and reduced productivity why is there resistance when it comes to health and safety legislation in this area?

Perhaps difficulties in understanding arise from the ‘traditional’ perspective in health and safety, based on risk management. Businesses deal with ‘risk’ and ‘risk management’ routinely in areas such as finance, strategy, and operations (among others). As such, the principles of risk management, which are based on being proactive, are not at all foreign to them. However, the same cannot be claimed for other key stakeholders involved in psychosocial risk management, such as occupational health services.

Experts working in occupational health services traditionally have a ‘reactive’ perspective to psychosocial illness, supporting individuals and organizations deal with problems they experience, and not designing a work environment that will prevent them from occurring. The approach employed to deal with psychosocial risks is very much focused on ‘mending harm’ and not sufficiently on prevention through managing risks.

Psychosocial risk management should not be approached solely through a health and safety perspective (and not solely from a human resource management perspective either since this often lacks prioritization) but from a strategic perspective both at organizational and at policy level.

10 tips for managing shift work Nov 11th, 2014

Shift work can have negative effects on a person’s health. For instance, working at night and sleeping during the day can disrupt the body’s natural circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are the body’s natural cycles that control a person’s appetite, sleep, mood and energy level.

Shift work can have negative effects on a person’s health. For instance, working at night and sleeping during the day can disrupt the body’s natural circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are the body’s natural cycles that control a person’s appetite, sleep, mood and energy level.Interfering with a person’s circadian rhythms can result in:

- stress;

- fatigue;

- depression;

- headaches;

- high blood pressure; and

- an increased risk of developing stomach ulcers and heart disease.

Shift work also has organisational risks. Workers are at their least competent and watchful at the end of a shift. Fatigued workers are more likely to make mistakes and to have poor concentration and response times. Workers at the end of a long shift who are responsible for part of a worksite might:

- leave the workplace in an untidy and dangerous way;

- fail to conduct proper handover for the next worker about to begin their shift;

- neglect to properly carry out a safety process; and

- fail to identify safety risks for themselves and other workers.

10 tips for managing shift work

Follow these 10 tips to effectively manage shift workers:

- Ensure that a worker’s work cycle includes no more than six consecutive 8-hour shifts or four consecutive 12-hour shifts.

- Keep night work to a minimum. Workers should be given as few night shifts in a row as possible.

- Make shifts shorter when the work is particularly hazardous or exhausting.

- Ensure that workers who work 12-hour shifts or night shifts do not regularly work overtime.

- Ensure that workers rarely work more than 7 days in a row.

- If possible, keep workers’ shift cycles consistent.

- Give adequate notice of roster changes.

- Ensure that workers have sufficient breaks during their shifts, particularly for those working long shifts and undertaking high-risk work.

- Give workers adequate time between the end of one shift and the start of another to rest and recuperate.

- Have a handover policy in place to ensure effective handover for the next worker.

Health care cost measures in measures in employees with and without Metabolic Sydrome and with and without sufficient physical activity Oct 28th, 2014

Productivity measures in employees with and without Metabolic Syndrome and with and without sufficient physical activity Oct 28th, 2014

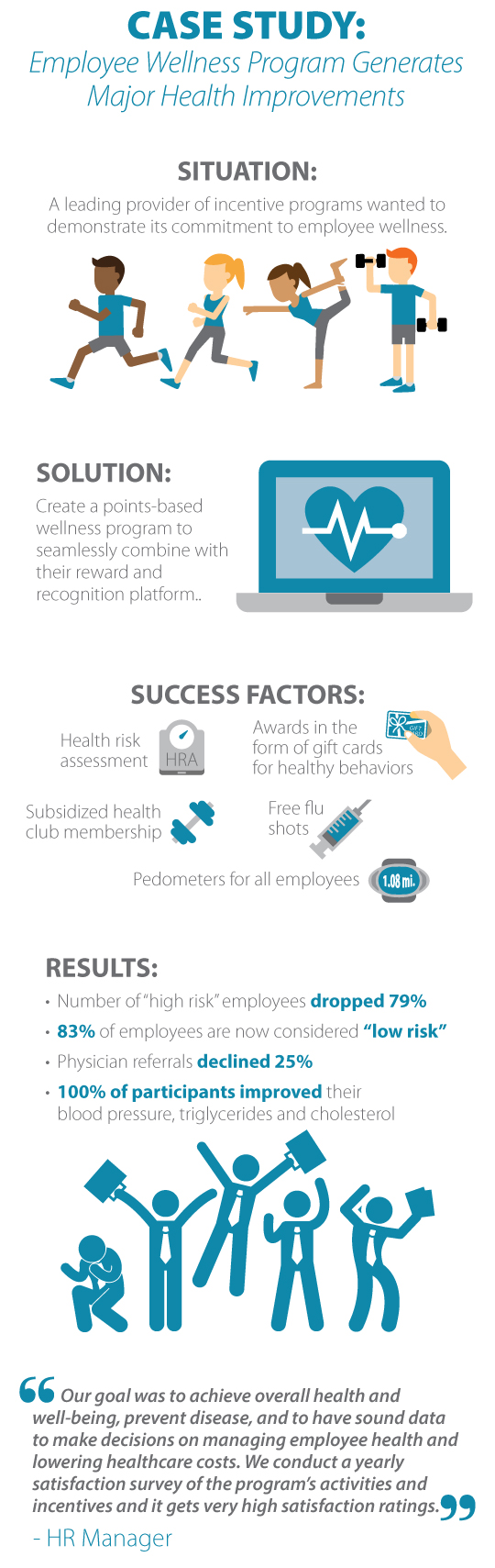

Workers who exercise lower health risks, cost less Oct 28th, 2014

This study looked at the impact of exercise on 4,345 employees in a financial services company. Roughly 30 percent of employees were high risk and suffering from metabolic syndrome, a dangerous cluster of risk factors associated with diabetes and heart disease.

This study looked at the impact of exercise on 4,345 employees in a financial services company. Roughly 30 percent of employees were high risk and suffering from metabolic syndrome, a dangerous cluster of risk factors associated with diabetes and heart disease.The study found that when the high-risk employees accumulated the government-recommended 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise a week, their health care costs and productivity equalled that of healthy employees who didn't exercise enough.

We can't control our family history and some health indicators such as cholesterol can be difficult to manage, but if individuals get enough exercise, the negative impacts of metabolic syndrome could be mitigated.

Employees with metabolic syndrome who exercised enough cost $2,770 in total health care annually, compared to $3,855 for workers with metabolic syndrome who didn't exercise enough.

Employees with metabolic syndrome who exercised enough cost $2,770 in total health care annually, compared to $3,855 for workers with metabolic syndrome who didn't exercise enough.With a bit of imagination, employers can develop and implement low cost interventions and programs that make it easy for workers to exercise on the job. Some examples include walking groups, signs reminding employees to take the stairs rather than the elevator, or developing and distributing maps of walking routes that fit into a lunch hour.

Central West Health and Rehabilitation has programs to assist this process, including services for remote workforces. Contact Us for more

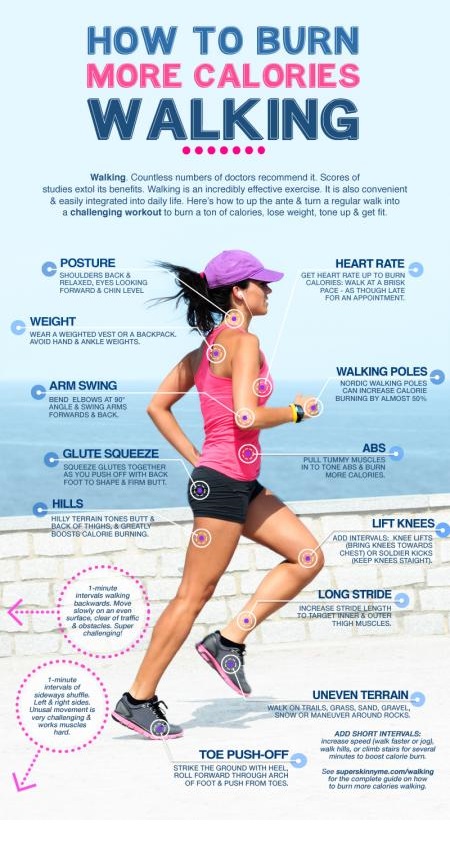

Infographic- Burn more calories walking Oct 17th, 2014

Predicting time on prolonged benefits for injured workers with acute back pain Oct 16th, 2014

Workers who are at low risk for chronic disability will most likely return to work (RTW) with limited assistance. Those at high risk for chronic disability may benefit from tailored interventions. If so, the burden of BP could be reduced through the early identification of those at high risk of chronic disability and delayed RTW.

Most of the existing literature relies on information gathered from injured workers, which is often limited to clinical factors. However, work-related BP is a multidimensional problem; therefore, predictive factors should be collected from several key actors [workplace partners, health-care providers (HCPs), injured workers, insurers] to capture the complex interactions that influence outcomes.

The following factors were predictive of a longer time on benefits:

- older age,

- greater physical demands in the workplace,

- employer doubt regarding the work-relatedness of the back injury,

- receiving a prescription for opioids during the first 4 weeks of the claim.

The following factors were predictive of a shorter time on disability benefits:

- union membership,

- availability of an early RTW program,

- positive recovery expectations on the part of health-care providers,

- being entered in a work rehabilitation program, and

- communication of functional ability to RTW

Implications

High risk individuals can be selected within the first 4 weeks following acute low back pain.

Early RTW planning and strong communication between the employer, and a trusted health care team improves outcomes.

Work debate spaces: Improve safety practices with employee input. Oct 15th, 2014

Safety relies on the ability of workers to assess the applicability of procedures and adaptations to carry them out. In order to progress, it is necessary to consider the safety approach as adaptive, dynamic, and developmental. Although the concepts around the development of a safety and safety culture are well developed, tools and methods that enable practitioners to ensure that the system in which they work are resilient and able to bounce back quickly to errors or other unexpected events are required.

Participatory approaches may play a key role. But how to develop participatory approaches that articulate the formal and the living organization? A possible way is the discussion and confrontation of points of view between different stakeholders of the organization around elements of the real work.

Work debate spaces (WDS)

To foster participatory approaches in safety it is necessary to develop means to consider the actual organization and interactions among workers. These are concepts developed by the approaches ‘Strategizing’ and ‘Work of Organization’.

Strategizing: This approach integrates the routines of meetings, discussions, or data processing in the definition and implementation of a ‘strategy’. It is important that the strategic issues of the organization are not decided and imposed by the leaders, but rather are the result of a daily construction with all stakeholders of the organization.

Work of Organization: This approach describes a living organization: occupational rules are developed by the employees in order to mitigate the defects of the formal organization, and to develop safety.

Both approaches consider an organization defined simultaneously by the leaders and by local and temporary regulations constructed by employees in the field. The questions they raise are needed to feed the managerial and strategic levels of the organization.

Articulating safety challenges is only possible with a working group to identify the situations that are particularly difficult to manage, to discuss them within the organizations and to propose changes.

WDS's are a time for discussion. The group advocates the discussion of work on a regular and protected basis, coordinated by a manager who does not belong to the direct hierarchy (e.g. Health and Safety Representatives). This method acts as a medium that deals with all the arrangements, compromises and adaptations that are required for safety system changes.

WDS permit not only the improvement of safety, but also help develop the competences of the employees, management and HR department with the bigger picture realities of health and safety. It allows safety to move beyond the traditional perimeter of the retrospective analysis of dysfunctions, and enter in learning dynamic starting with field situations. It allows the development of safety by different levels in the company, and progresses the organization beginning with experiences within the organization itself. This permits the development of an enabling environment for safety

It is necessary that the executive committee be engaged in the process by supplying the technical, organizational, and human means so that the WDS can be instigated. A preliminary phase is necessary, based on observations and interviews with workers, to engage the elements for the development of the WDS. Within these spaces, some conditions are defined so that people can experience the improvement proposals: a discussion based on real work activity, a joint elaboration and evaluation of solutions based on a dynamics of confrontation.

What should you do if a worker claims their work is unsafe to perform? Oct 15th, 2014

A worker who refuses to perform work because of genuine safety concerns cannot be liable for industrial action.

If a worker complains of a safety risk in the work they perform, undertake the following steps:

- Ask the worker to identify the hazard and the risk it poses;

- Control the risk by eliminating the hazard or implementing risk controls; and

- Ensure workers are fully trained in the new work procedures.

If the hazard can’t be controlled, stop the process if possible and consider what alternative safe work you can offer workers.

If a union threatens industrial action in relation to a health and safety concern, notify the union of the steps you have taken and engage them in any dispute resolution processes you take.

If the worker has a health and safety representative or if your workplace has a health and safety committee, they must also be included in the dispute resolution process.

Next- What if the issue is difficult to fix?

Sick leave patterns in common musculoskeletal disorders Oct 14th, 2014

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are the most common causes of severe long-term pain and physical disability and have a major impact on society.

Sick leave is an important public health problem with both social, economic and health related consequences for the individual as well as social and economic consequences for society, and MSD’s are one of the most common reasons for work disability and sick leave.

20 251 sick leave periods were issued for 16, 673 with a mean (SD) age of 43. The main purpose was to give a descriptive overview of sick leave patterns in different diseases within the group of MSDs, including all doctors prescribed sick leave. The aim was to get comparable estimates of duration, age and sex distribution and patterns of recurrent sick leave for the different subgroups.

Adjusted for age, the mean number of days per sick leave period was 26 days for low back pain and 27 days for myalgia (i.e. other soft tissue disorders not classified elsewhere). Disc disorders and rheumatoid arthritis had the longest periods with a mean of 150 and 147 days respectively. For hip and knee osteoarthritis the mean was 81 and 116 days respectively

The distribution of number of sick leave periods, over age categories, and between men and women, was different for the different disease groups. For back disorders, the total number of sick leave periods was highest in the age groups 40–44 and 45–49, with a similar pattern for women and men. The number of sick leave periods for knee and hip osteoarthritis peaked in the older age groups with a predominance of men in the hip osteoarthritis group. Myalgia had a more even distribution over the age categories with similar patterns for men and women.

25% had more than one sick leave period during the two years. Out of the six studied disease groups, individuals with rheumatoid arthritis had the greatest share of recurrent sick leave periods (34%) despite also having a greater share of long sick leave periods. The other conditions with typically long sick leave periods, e.g., disc disorders and hip osteoarthritis, had less recurrent sick leave (15 and 18% respectively), while typical conditions with short sick leave periods, e.g., back pain and myalgia, had more episodes of recurrent sick leave.

Exercise and start talking: tips to help improve FIFO workers’ mental health Oct 13th, 2014

FIFO workers are being urged to implement six simple strategies in order to stay mentally healthy.

Avoiding the wages trap, keeping the lines of communication open and staying physically fit are among the steps workers can take to improve their mental health, according to industry support group Mining Family Matters.

Numerous studies into the wellbeing of FIFO workers has found stress, anxiety, divorce, drug and alcohol use and a sense of helplessness are prevalent among the workforce.

A study last year by Lifeline WA and Edith Cowan University psychologists, found a number of issues affecting FIFO workers’ mental health. In August the West Australian parliament unanimously backed an inquiry into the link between FIFO mining rosters and suicide.

Mining Family Matters has suggested the following strategies:

- Be honest about how you're feeling and tackle problems as a team. Many problems that arise are symptoms of the FIFO lifestyle, rather than relationship problems.

- Set shared goals.

- Don't assume that your life is tougher than your partner's. (Life is not a competition - you're both exhausted.)

- Get financial advice to ensure good wages are saved and invested wisely, instead of being trapped by large debt.

- Exercise regularly - it will improve the health of both body and mind.

- Try to keep the lines of communication open when you're apart (and if you don't feel like talking, explain why in a loving way).

Video - Wheelchair Basketball Fitness Circuit Oct 11th, 2014

The most effective worksite health promotion program Oct 9th, 2014

These are tips that will assist you in making the most effective worksite health promotion program you can. Use them alongside the 8 steps to an effective health promotion program, and you will be halfway there!

An effective health promotion program will do the following:

- Be coordinated by a person with the necessary skills and resources to commit to the project.

- Have the long-term commitment of the company (workers, management, directors) to achieve long-term results.

- Be integrated with the operations of the company.

- Have the capacity to adapt when the needs of the business or its workforce change.

- Be available to everyone in the company.

- Involve consultation between managers and workers to guide the direction of the program.

- Use resources within the workplace, as well as those available outside the workplace (such as community resources), to reduce the cost of the program.

- Be a mix of low-cost strategies with higher-cost and commitment strategies.

- Reinforce and support the company health and safety plan.

- Use external experts and agencies for addressing specific problem areas within your business, e.g. quitting smoking.

- Involve senior management participation in the activities, exercises and strategies that make up the program.

- Be promoted to workers to:

- encourage participation voluntarily;

- increase understanding of the program and its advantages; and

- increase awareness and involvement in improving the program.

- Demonstrate the benefits of working with the company to potential workers.

- Not look down upon workers for not participating.

- Be reviewed regularly and reported back to senior management.

Remember, there are many factors that can affect a person’s health and well-being, both physically and psychologically. Some of these factors will exist within the workplace, e.g. relationships with colleagues, working environment, level of job satisfaction, and some of these factors will exist outside the workplace, e.g. personal relationships, living conditions, lifestyle choices.

Central West Health and Rehabilitation can provide cost effective assistance. Contacts

So what can we include in a worksite health promotion program? Oct 9th, 2014

Worksite health promotion programs should be developed to suit the nature of your business and the needs of your workers. Therefore, a health promotion program that fits one company will not necessarily fit the next.

So what can you include in your health promotion program?

Some options are easy to implement, others take more time and resources. Here are a few examples of what you could do in your workplace:

develop health and safety policies and procedures that have a commitment to the wellbeing of your workers at their core;

develop health and safety policies and procedures that have a commitment to the wellbeing of your workers at their core;- create a supportive working environment where a work/life balance is promoted;

- encourage positive social interaction and personal skill building in your workers through social events and participation;

- always provide non-alcoholic options at work-related functions and educate your workers on alcohol and drug misuse;

- inspire your workers and encourage learning with workshops and guest speakers during lunch breaks;

- provide health services to workers such as physical health checks, eye tests, flu vaccination,

- provide access to a range of health resources, including specialist information from external agencies;

- create awareness by holding seminars on issues such as stress management, healthy eating or quitting smoking;

- provide showers, changing rooms and bicycle racks to aid and encourage a physical activity for your workers' commute;

- organise a corporate rate for your workers to join the local gym;

- provide filtered water and facilities for preparing healthy lunches;

- provide access to counselling for smokers who want to quit; and

- encourage participation in a organised community events such as fun runs.

Remember, the level of resource commitment your business makes to these kinds of programs is up to you – there is no right or wrong answer but the most important thing to remember is that when your workers are feeling good they will be performing well and that has many benefits for your business.

Video - Diabetes ABCs Oct 9th, 2014

Work disability among workers with knee arthritis Sep 22nd, 2014

The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis (OA) among individuals active in the workforce will increase considerably in the next generation and a significant percentage of these individuals are expected to experience work disability because of this disease.

Knee OA is responsible for prolonged sick leaves and early retirement in a small percentage of workers; however, many workers will have the disease for a long time and remain active in the workforce, not achieving their optimal productivity. Knee OA seems to affect partial work disability or ‘presenteeism’, defined as the loss of work productivity in terms of quantity or quality because of an illness or an injury in individuals who are present at their job, rather than absenteeism.

The above review was to summarize the existing knowledge on:

(a) work disability risk factors;

(b) efficient interventions to reduce work disability in individuals with knee OA.

Risk factors

The only study (Bieleman et al., 2013) that answered the research question on work disability risk factors provided data from a large-scale prospective cohort of good quality. On the basis of this study, age and previous work absence episodes can be viewed as predictors of work disability for OA patients. Bieleman et al. mainly focused on physical personal factors; however, it is now well established that psychological factors such as perceived job strain, social support from co-workers and supervisors, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy influence work participation among individuals with RA and other MSK disorders. Work environment (physical work demands, work adaptation) could also play a major role.

Interventions

Only two studies on work disability intervention were found, the results of these studies converged to conclude that compared with standard care interventions, education-based interventions seemed to be more effective in reducing work disability.

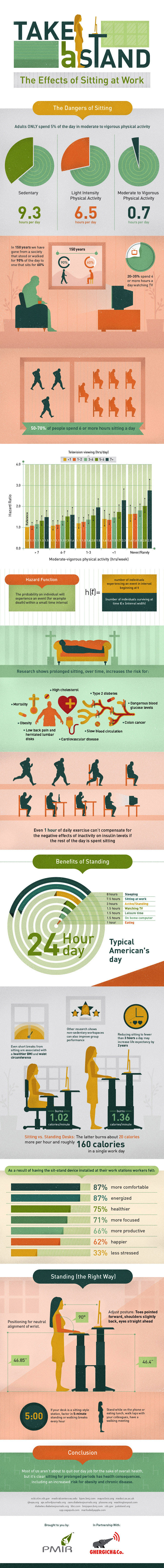

Strategies to help you stand up, sit less and move more Aug 29th, 2014

Many advanced organisations are implementing strategies to reduce prolonged sitting. Some risk reduction strategies, such as introducing standing meetings, are costless, while other strategies have a cost. Changes to work systems can reduce sedentary time. Alterations to the individual physical environment (eg, sit–stand workstations or active workstations) and combined approaches (including individual, environmental and organisational changes) have achieved substantial reductions in total occupational sitting time and prolonged unbroken sitting time.

Here are 12 strategies to help you stand up, sit less and move more

- Walk over and talk to colleagues instead of emailing them.

- Remove bins and/or printers from your office and use central ones.

- Dispose of waste and/or collect printing more frequently.

- Drink more water so you have to go to the water cooler (and bathroom) more often.

- Use a bathroom that is further away.

- Step outside for fresh air.

- Use the stairs instead of the lift.

- Use an active way of commuting to work (walk or ride a bike, stand up in the train, or stand up to wait for your train/bus).

- Park your car further away from your workplace and have a short walk, or park in short-term parking so you have to walk back to move your car.

- Have lunch away from your desk.

- Walk laps of the floor at regular intervals to break up the day.

- Walk around the neighbourhood at lunch. You can mark out two or three timed walking routes to fit into your working day and promote variety.

Excessive occupational sitting is not a “safe system of work†- Is it time to implement risk control strategies Aug 29th, 2014

Being able to work usually has a positive impact on health. However, changes in the physical demands of work and increased use of computers have led to many workers now being employed in sedentary jobs. While these have traditionally been thought of as safe work environments, recent evidence suggests this mode of work — often involving long uninterrupted periods of sitting — may be hazardous, contributing substantially to the growing chronic disease burden associated with obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Being able to work usually has a positive impact on health. However, changes in the physical demands of work and increased use of computers have led to many workers now being employed in sedentary jobs. While these have traditionally been thought of as safe work environments, recent evidence suggests this mode of work — often involving long uninterrupted periods of sitting — may be hazardous, contributing substantially to the growing chronic disease burden associated with obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer.Importantly, being sedentary (ie, too much sitting) is not the same as being physically inactive. Insufficient client physical activity is defined in the public health context as not meeting the guidelines to accumulate at least 2.5 to 5 hours of moderate-intensity physical activity per week. Both physical inactivity and sedentary time have an impact on health: physical inactivity is estimated to account for 5.5% of all-cause premature mortality, and excessive sitting time, after adjusting for physical activity, accounts for 5.9%.

Even if workers meet physical activity guidelines (i.e. are physically active), they can still have high exposure to sedentary time!

Work health and safety laws in Australia and other jurisdictions require employers to provide a "safe system of work". For example, section 19 of the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 states that the "primary duty of care" is to "ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety of workers" by, among other things, "provision and maintenance of safe systems of work".

This has lead a number of experts voice the following (Straker et al, 2014):

a) the systems of work commonly observed in contemporary offices demonstrate a high likelihood of excessive sitting hazard;

b) the degree of harm associated with this hazard is likely to be substantial;

c) the evidence for this is now widely known;

d) there are available ways to minimise the risk; and

e) the cost of these strategies is proportionate to the risk.

For these reasons many advanced organisations are implementing risk control strategies. Some risk reduction strategies, such as introducing standing meetings, are costless, while other strategies have a cost. Changes to work systems can reduce sedentary time. Alterations to the individual physical environment (eg, sit–stand workstations or active workstations) and combined approaches (including individual, environmental and organisational changes) have achieved substantial reductions in total occupational sitting time and prolonged unbroken sitting time.

In an aging population, those organisations that don’t may find themselves having to catch up as legislation and Health Professionals start to recognise available evidence suggesting contemporary offices are failing to provide a “safe system of work” for their patients.

For example, Doctors should be prescribing behaviour to reduce occupational sedentary exposure where this may exacerbate, or be exacerbated by, an existing medical condition. A doctor who is aware that a patient has a prolapsed disc in the spine would require the patient to refrain from lifting heavy objects at work. In the same way, a doctor who is aware that a patient’s cardiovascular condition necessitates remaining active and avoiding excessive sedentary exposure should inform the patient and employer of the need for the patient to regularly move to maintain wellbeing!

Factors influencing return to work after hip and knee replacement Aug 27th, 2014

Hip and knee arthritis causes significant problems in the working-age population and can lead to a reduced quality of life, change in employment or unemployment. The 10th National Joint Registry reported that 18–20% of patients undergoing hip and knee replacement in England and Wales were under the age of 60 years (NJR. National Joint Registry for England and Wales 10th Annual Report, 2013. www.njrcentre.org.uk)

Heavy lifting and bending have been reported as important factors in the development and progression of arthritis. The effect of arthritis on employment depends on the type of work usually performed, with manual or lifting jobs associated with increased levels of unemployment due to arthritis. In addition to a loss of employment, arthritis has also been associated with a prolonged sickness absence or a change in the type of work performed.

Studies have quantitatively assessed the role of surgery in returning the patient to work after joint replacement. Joint replacement may enable patients to continue working, which may be more cost-effective in the long term as patients remain economically productive members of the society. However literature is sparse regarding factors affecting return to work after knee or hip replacement.

The above review of qualitative and quantitative literature aimed to address the following questions (See table 2):

1) What are the employed patient’s expectations from a joint replacement before and after surgery?

2) Who is most at risk of not returning to work after joint replacement surgery?

3) What external factors are important to help patients return to work?

4) Does age of the patient determine their ability/motivation to return to work?

5) Are patients able to return to work at the same level?

Scientists Discover Area of Brain Responsible for Exercise Motivation Aug 27th, 2014

Scientists at Seattle Children’s Research Institute have discovered an area of the brain that could control a person’s motivation to exercise and participate in other rewarding activities – potentially leading to improved treatments for depression.

Researchers have discovered that a tiny region of the brain – the dorsal medial habenula – controls the desire to exercise in mice. The structure of the habenula is similar in humans and rodents and these basic functions in mood regulation and motivation are likely to be the same across species.

Exercise is one of the most effective non-pharmacological therapies for depression. Determining that such a specific area of the brain may be responsible for motivation to exercise could help researchers develop more targeted, effective treatments for depression.

Changes in physical activity and the inability to enjoy rewarding or pleasurable experiences are two hallmarks of major depression. But the brain pathways responsible for exercise motivation have not been well understood.

The study used mouse models that were genetically engineered to block signals from the dorsal medial habenula. Compared to typical mice, who love to run in their exercise wheels, the genetically engineered mice were lethargic and ran far less.

In a second part of the studye, the mice could “choose” to activate this area of the brain by turning one of two response wheels with their paws. The mice strongly preferred turning the wheel that stimulated the dorsal medial habenula, demonstrating that this area of the brain is tied to rewarding behaviour.

Infographic - Sitting and Injury Aug 24th, 2014

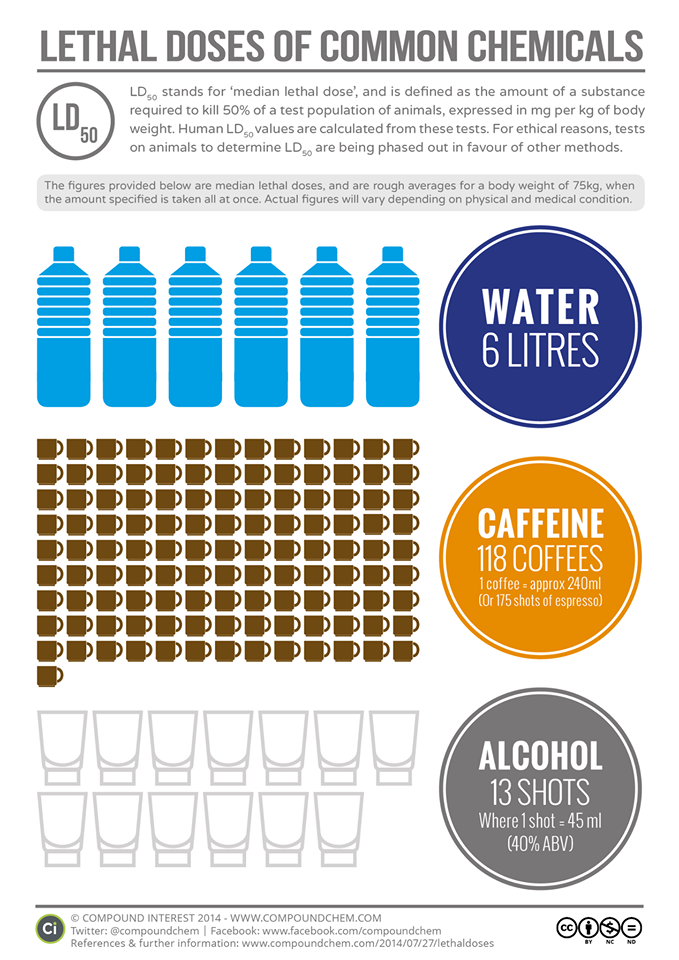

Infographic - Coffee, Alcohol, Water Aug 22nd, 2014

Infographic - Injury First Aid Aug 18th, 2014

Hypoglycemia Aug 5th, 2014

Hypoglycaemia is most common in people who inject insulin or are taking tablets to manage their diabetes. It is not a problem for those who do not take medication to manage their diabetes. Talk to your doctor or trusted health professional (diabetes educator, exercise physiologist, pharmacist etc) to find out your risk.

Video - Blood Presure Aug 4th, 2014