P: (08)9965 0697 F: (08)9964 7528

News

One in five serious workplace injuries involve a tradie Aug 2nd, 2014

Startling figures from the Australian Physiotherapy Association's latest health report, released today, show tradies have among the highest number of injuries, musculoskeletal conditions and other health and safety risks of any profession. Many from smaller businesses who are harder for national health and safety initiatives to reach.

Released as part of Tradies National Health Month, the Stop Trading Your Health Away report shows nearly one in five serious workplace-related injuries involve a tradie, making them one of the most affected professions in Australia.

Musculoskeletal health costs $20.9 billion annually in direct health and lost productivity costs in Australia.

Within the industry, construction workers are currently claiming 34 per cent of workers’ compensation claims. More than half of these claims were related to muscular stress while handling a range of materials, tools or other equipment.

Tradies are also among one of the largest proportions of occupations with the highest incidence of early retirement. Statistics show that tradies are 35 per cent to 50 per cent more likely to retire before the age of 60 compared to professional workers.

Is Manual Handling Training Worth it?

Video - Nerve Pain Aug 1st, 2014

Video - Phases of Pain Jul 31st, 2014

Case Study - Concord General Hospital, Sydney Jul 27th, 2014

Some injuries take longer to heal due to the nature of the injury and management. We have generally found three types of disability groups have come to light over the years.

The first is the short duration claim where the patient has a well-defined acute episode (i.e. flu, strain or sprain). These cases will return to work often with minimal intervention.

The second (and often most difficult) group represents the patients with sub-acute or progressive diseases or injuries. This population often needs help with ensuring the medical interventions are enough to progress back to health. They may need help in finding their way through the health care maze and psychosocial issues can be a major barrier to RTW.

The third group are those with terminal or debilitating diseases, such as Chronic Pain, Cancer or Multiple Sclerosis, that may eventually prevent return to work.

Concord General Hospital in Sydney is a self insurer, who in 2003-4 found themselves with a huge number of open claims (~300), and a spate of very difficult cases who went on to have chronic pain syndromes. The organisation felt they were failing injured workers and that something needed to change.

The initial step was to change their existing rehabilitation policy. They developed a database to track workers from notification to finalisation. They developed resources such as suitable duties lists for a majority of departments, and increased the role of managers in the rehabilitation process. They also took steps to increase the level of communication by having regular meetings between supervisors and managers of major departments to review claims and provide comparative data.

The consensus was that the first 4 weeks after an incident/injury was the answer, – after that you start to lose control! They instigated a rapid assessment and early intervention process, which included an assessment psychosocial risk (i.e. Yellow Flags). The idea was that high risk individuals needed to be identified in the first week/s. Nothing different needed to be done; only it needed to be done earlier. It was also important that the GP was in control of the whole process through consultation and approval.

The first question to answer was; “can these high risk individuals be found early, and if so, do they actually costs more?” Injured workers filled out a psychosocial risk questionnaire and were followed through until they returned to work with a final certificate. Each injured worker was categorised and claim costs were reviewed and compared across the high, medium and low risk groups.

The answer to Question 1 appeared to be a resounding YES! (see image)

The next question was then “what can be done about it?” Concord’s approach was to; (a) activate an independent Vocational Rehab Provider within first 2 weeks; (b) complete an independent psychological assessment, and subsequent treatment within 2 weeks; (c) complete an independent Medical Consultation within 4 weeks; (d) have the file reviewed if not returned to work within 4-6 weeks.

The emphasise of the above approach did not appear to do anything different to what usually happens, it simply did it much earlier in the management process.

The results were quite impressive; primarily there was a 25% reduction in the costs of each ‘high risk’ claim. This equated to a $4331.00 saving per high risk claim. (see image)

Implications:

There is a significant difference between the 20% in the “high risk” category and the other 80% who manage pretty well with ‘usual care’.

Psychosocial risk factors (i.e. ‘Yellow Flags’) predict the cost of a workers compensation claim within 48 hours regardless of what or where the injury occurs.

The provision of an early and aggressive assessment and intervention, lead by a trusted GP can reduce costs in high risk claims.

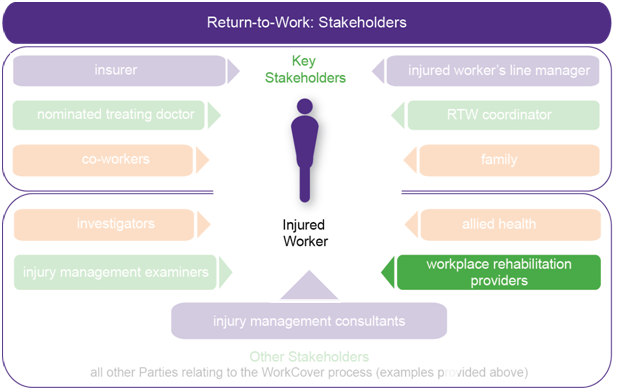

Vocational Rehabilitation - What do they do? Jul 26th, 2014

Approved Vocational Rehabilitation Providers (Voc Rehab) can assist an injured worker if there are problems with the return to work process. Voc Rehab providers are commonly health professionals such as occupational therapists, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists or psychologists who ‘generally’ have expertise in addressing the physical, psychological and/or workplace barriers that may prevent an injured worker returning to work.

Workplace rehabilitation providers are approved by WorkCover WA and have the qualifications, experience and expertise appropriate to provide timely intervention with services based on the assessed need of the worker and the workplace.

A voc rehab provider is essentially an injury management co-ordinator. Voc Rehab will attempt to deliver an appropriate professional return to work program when the situation requires an external provider (see below).

If an initial assessment indicates that rehabilitation services are recommended, the rehabilitation provider must discuss the findings of the assessment with the employer, the injured worker and the treating medical practitioner.

The rehabilitation provider should give a copy of their plan to the injured worker, employer and treating medical practitioner. The insurer should also receive a copy of the service plan; in most instances, the insurer will provide approval for payment of rehabilitation expenses as part of the claim.

In all circumstances, employers should remain the workplace decision maker regarding return to work activities.

What rehabilitation services may be recommended?

Rehabilitation providers can provide any of the following services in helping workers return to work:

- support counselling

- vocational counselling

- purchase of aids and appliances

- case management

- retraining criteria assistance

- specialised retraining program assistance

- training and education

- workplace activities

- placement activities

- assessments (functional capacity, vocational, ergonomic, job demands, workplace and aids and appliances)

- general reports

The worker is unable to carry out pre-injury duties and there is a need to identify alternative or modified duties with either the same employer, or with a new employer.

There is a need to complete a practical assessment of a worker’s capacity to return to work (for example, when there are conflicting opinions of the worker’s physical or psychological capacity to return to work; or there are reports of ongoing symptoms when the worker is at work).

The worker is experiencing problems associated with returning to work (for example, personality clashes with worksite injury management staff.).

Modifidations are required to the workplace are being considered to assist the workers return to work (for example, special lifting equipment or special seating arrangements).

There is a need to assess the suitability of a return to work program with a new employer if this is identified by the injured worker, employer and treating medical practitioner as the new rehabilitation goal.

There is a need to determine whether retraining is likely required. (back)

Who pays for a workplace rehabilitation provider?

Vocational rehabilitation providers are approved by WorkCover WA and their costs are covered by the Prescribed Amount in every workers’ compensation claim. Costs may vary according to the services they provide, but the maximum amount they can charge is determined by WorkCover WA and reviewed annually. These costs will add to your yearly claim costs, used to determine your insurance premiums.

How to activate a referral to a workplace rehabilitation provider?

A referral may be completed on the Workplace Rehabilitation Referral Form or may be made on the worker’s First or Progress Certificate of Capacity.

Note: Injured workers have the right to choose their vocational rehabilitation provider, even when the referral is made by a medical practitioner or employer.

August is Tradies National Health Month Jul 25th, 2014

Throughout the month of August the APA and Steel Blue will run Tradies National Health Month – a health awareness campaign to educate tradies on the importance of full body health and safety. The Australian Physiotherapy Association and Blue Steel have teamed up to create a month that focuses on full-body health and safety for tradies to improve awareness and support in this area.

Click the Link below to Play the Game - Pain Breaker

These organisations have also developed a wide array of great handouts and resources, which we have provided to help Tradies look after their minds and bodies. A few are provided below, many more are avaliable at the website.

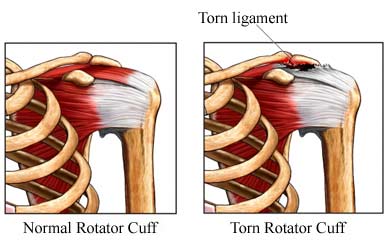

Return to work following Shoulder Surgery Jul 24th, 2014

Rotator cuff tears are a common shoulder problem affecting more than half the population older than sixty years of age. Surgery may be used to treat a rotator cuff disorder if the injury is very severe or if nonsurgical treatment has failed to improve shoulder strength and movement sufficiently.

Rotator cuff tears are a common shoulder problem affecting more than half the population older than sixty years of age. Surgery may be used to treat a rotator cuff disorder if the injury is very severe or if nonsurgical treatment has failed to improve shoulder strength and movement sufficiently.Surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff tendon usually involves; (a) removing loose fragments of tendon, bursa, and other debris from the space in the shoulder where the rotator cuff moves (debridement); (b) making more room for the rotator cuff tendon so it is not pinched or irritated. If needed, this includes shaving bone or removing bone spurs from the point of the shoulder blade (subacromial smoothing); (c) sewing the torn edges of the supraspinatus tendon together and to the top of the upper arm bone (humerus).

Acevedo etal, 2014 attempt to determine common clinical practices among 372 shoulder and elbow surgeons with regard to rotator cuff repair and management, including return to work practices. 89% of the surgeons surveyed suggested dedicating over half of their practice to the treatment of shoulder pathology.

Regards Healing Rates

Half of surgeons suggested 80% to 90% healing rate for small tears(<2cm).

70% to 43.1% of surgeons suggest 80% healing rate for large tears (2 to 4 cm).

49% of surgeons suggested 50% to 60% healing rate for massive tears (>5 cm).

70% of survey participants told their patients that their shoulder would be 'as good as it gets' one year after surgery.

A large number of surgeons (55.3%) do not allow their patients to drive a car until the arm is out of the sling full time.

91.3% of respondents reported that they would perform surgery on a current smoker despite the body of evidence showing the relationship of smoking and rotator cuff disease, and smokers having a higher retear rate. Surgeons often have a difficult time getting patients to quit smoking and smokers are still able to attain successful outcomes in most cases, albeit with higher risk of failure and longer recovery times.

Regards Lifting Restrictions

37.3% of surgeons recommended a lifting limit of 0.5kg at one month, and 29.4% allowed 4.5kg at three months. By six months and one year after surgery, a majority of respondents advised their patients to let pain be their guide as a limit to lifting (62.7% and 72.8%, respectively).

Regards Return to Work

Surgeons were asked when they allowed their patients to return to work at a sedentary job and to a manual labor job after repair of small, large, and massive rotator cuff tears.

The most common response in regard to return to a sedentary job was one to two weeks for small tears (41.2%), large tears (38.2%), and massive tears (34.3%).

For a manual labor jobs, two responses were most common; 34.7% allow patients to return to work at three months, and 35.6% allow return to work at four months after repair of small tears. Additionally, 17.8% of respondents allowed return at six months for small tears. After repair of a large tear or a massive tear, respondents most commonly allow their patients to return to manual labor at four months (29.4%) or six months (34%), respectively.

In regard to patients with Workers’ Compensations claims, a large percentage of surgeons do not allow a return to manual labor until six months postoperatively for small tears (56.6%). There was a consensus with surgeons who allow return to work after six months for large tears (68%). After repair of a massive tear, 40.2% allow return to work after at least six months, but 38.2% responded 'maybe never.'

Return to work following routine Knee Arthroscopy Jul 19th, 2014

Knee injuries are a common workplace problem and Knee arthoscopy is the most common procedure performed by orthopaedic surgeons (Salata et al, 2010). However there is scanty literature documenting expected recovery duration (often suggested as anywhere from nine days to four weeks for routine uncomplicated arthroscopy).

The above study of a military population noted that while patients were able to walk around without any support at two weeks post surgery, 88% still had restriction to activities of daily living (and therefore work) because of knee related problems. Function improved gradually over the following 12 weeks. At 6 weeks 91% resumed their preinjury status which reached 94% in eight weeks.

Predictors of poor outcomes include total removal of the meniscus or removal of the peripheral meniscal rim, lateral meniscectomy, degenerative meniscal tears (more common in older age groups), presence of chondral damage (more common in older age groups), presence of hand osteoarthritis suggestive of genetic predisposition, and increased body mass index.

Psychosocial factors (anger, depression, social support [i.e. workplace support]) play a significant role in recovery and are predictive of surgical outcomes (Rosenberger et al, 2006). Patients undergoing surgery must cope with the psychological and physical stress that often accompanies injuries and surgical procedures. In addition, patients must cope with the demands of the recovery process, which likely include managing postoperative pain and limitations in physical functioning (Rosenberger et al, 2004).

Implications

Following routine knee arthrscope the majority of workers should have capacity for 'suitable' modified duties by 2 week. However remember some patient will still be having considerable difficulty with tasks of daily life such as dressing, climbing stairs and getting up from sitting.

The majority of workers should be able to complete normal duties by 6-8 weeks following surgical date. However, some 6-10% still may need some duty modification beyond this.

Those at risk of a longer recovery can be predicted pre-surgically or early post surgically by the following:

- Age

- Type of procedure (full meniscus removal, peripheral meniscus lession, cartlidge damage and or microfissuring)

- Poor Lifestyle factors (High BMI, current smoker)

- Psychosocial factors (anger, depression, poor social/workplace support)

Infographic - Costs of Unhappy Employees Jul 18th, 2014

Video - Mentally Healthy Small Business Jul 18th, 2014

Cost savings from early ergonomics involvement in projects Jul 17th, 2014

Fortunately, properly planned and implemented ergonomics projects usually do result in significant economic benefits, and the literature consistently has shown that the earlier there is professional ergonomics participation in workplace design, the less costly is the effort.

For example, a number of studies have suggested the ergonomics portion of the engineering budget increases from about 1% of the budget when ergonomists are brought in at the beginning of a development project, to more than 12% when brought in after the system is put into operation.

This increase is believed to happen when ergonomists are brought in late in the project because serious human–system interface problems have surfaced that require major retrofits in order to correct them. A second major cost saving of early, or pre-emptive, ergonomics involvement can be in reducing the total cost of the design budget.

Personnel-related benefits from pre-emptive ergonomic involvement include:

Increased output per worker- Increased output per worker can be done for improvements in workplace design, hardware product design, software design and work system (macroergonomic) design.

Reduced error rate- Because correcting errors takes time, reduced errors frequently translate into increased productivity. Reducing errors also translates into fewer, accidents, and resultant reductions in equipment damage, personnel injuries, and related costs.

Reduced accidents, injuries, and illness- One of the most frequently encountered benefits. For example in one reported case study an ergonomically designed pistol grip type of knife was introduced to replace a conventional straight handle knife for deboning chickens and turkeys in a poultry packaging plant. This enabled the employees to de-bone the foul without having to significantly deviate their wrists, as was the case with the conventional knife. The resulting reduction in cases of carpal tunnel syndrome, tendonitis, and tenosynovitis translated into a saving in workmen’s compensation of $100,000 per year.

Reduced absenteeism- Reductions in lost time from persons failing to show up to work for reasons other than accidents, injuries, or illness, already noted, also is a common outcome of effective ergonomic interventions. Reduced absenteeism also can result in a productivity increase.

Reduced turnover- When ergonomic interventions improve the quality of work life, it is not uncommon to see a reduction in turnover rate, which can represent a significant financial benefit.

Reduced training time- Reductions in training requirements may come about because work system changes result in easier to perform functions and processes that require less time to learn. Alternatively, training requirements may be reduced because of:

(a) less turnover,

(b) reductions in lost time from accidents and injuries,

(c) less absenteeism, or

(d) because fewer people are required to perform a given function

Reduced skill requirements- Improved job designs and related work system processes may also result in reducing the skill requirements required to perform some jobs

Reduced maintenance time- Ergonomic improvements to jobs, worksites, equipment, or work systems can result in reducing the system’s maintenance requirements, thus requiring fewer maintenance personnel.

9 tips to reduce the risks for an ageing workforce Jul 17th, 2014

Australia’s population will both grow strongly and become older in the medium term. This population growth and ageing will affect labour supply, economic output, infrastructure requirements and governments’ budgets, and has lead to the gradual increase in the retirement age from 65-70 for those people born after 1965.

Australia’s population will both grow strongly and become older in the medium term. This population growth and ageing will affect labour supply, economic output, infrastructure requirements and governments’ budgets, and has lead to the gradual increase in the retirement age from 65-70 for those people born after 1965.As for safety on the job, workers who are older actually tend to experience fewer workplace injuries than their younger colleagues. This may be because of experience gathered from years in the workplace, or because of factors such as increased caution and awareness of relative physical limitations.

This caution is well-founded. When accidents involving older workers do occur, the workers often require more time to heal, underscoring the need for a well-planned return to work program.

Also evidence suggests incidents affecting older workers are more likely to be fatal. A recent Safe Work Australia document suggested people over 65 have a higher fatality rate (7.73 fatalities per 100,000 workers) than their young work collegues (0.98 fatalities per 100 000 workers). This underscores the need for employers to be mindful of how best to gradually adapt the conditions of work to protect workers as well as explore opportunities for preventative programs that can maintain or build the health of employees through their working life.

Here are 9 tips you can use to eliminate or reduce the risks posed to older workers in your workplace:

- Ensure that a person (regardless of age) is suited to the task and can carry it out safely; Pre-employment Physical Assessments are vital.

- Adapt tasks to suit older workers, e.g. an older worker with reduced physical strength may spend more time operating machinery than labouring;

- Rotate physically demanding or repetitive tasks;

- Provide ergonomically-designed work area and workstations for all workers;

- Regularly assess stress levels of workers and implement stress management training if required;

- Train all workers in injury prevention strategies (it is important to keep in mind that as you age, the pace and way that you learn changes, meaning that training requirements may be different for older workers and training may require repetition);

- Ensure workplace lighting is adequate for the job at hand;

- If possible, offer older workers flexible work arrangements, (e.g. reduced hours, fixed term contracts, working from home); and

- Consult workers about where they are having trouble and keep them informed about what you are doing to reduce the risks.

Video - Low Back Pain Jul 16th, 2014

Doctors With a Special Interest in Back Pain Have Poorer Knowledge About How to Treat Back Pain Jul 16th, 2014

Doctor surveys continue to demonstrate that general practitioners only partially manage low back pain (LBP) in an evidence-based way. This is despite increasing evidence that positive advice to stay active and continue or resume ordinary activities is more effective than rest and early investigation and specialist referral are unwarranted in the majority of cases. In part, this may reflect physician knowledge and beliefs, although physician behaviour may be influenced by many factors including patient expectation and other psychosocial factors.

Providers treating LBP may hold alternative beliefs regarding the association of pain and activity that may influence their practice behaviour. The preparedness of the clinicians to change may be another important barrier that has not been well studied to date.

The aim of the above study was to determine whether general practitioners’ beliefs about LBP differ according to whether they have a special interest in back pain, musculoskeletal medicine or occupational medicine; and whether these beliefs are modified by having had continuing medical education (CME) about back pain in the previous 2 years.

The results found that GP’s that suggested a ‘special interest’ in back pain were more likely to provide back pain management contrary to the best available evidence. GP’s with a special interest in occupational medicine and physicians with recent Continued CME about back pain had significantly better back pain management beliefs.

Implications

Many other factors besides the employee's medical conditions affect outcomes– e.g. organizational, work-environmental, and social. Providing employees a preferred medical provider and building a relationship with them by presenting them with appropriate and helpful information can improve not only return to work, but also patient management.

Safe Work Australia - Worker fatalities Australia 2013 Jul 15th, 2014

Data has been released by Safe Work Australia. The aim of this report was to highlight the number of people who died in 2013 from injuries that arose through work-related activity.

In 2013, 191 workers were fatally injured at work. This is 16% lower than the 228 deaths recorded in 2012 and 39% lower than the highest number of worker deaths recorded in the series in 2007. Most of the decrease from 2012 to 2013 was due to a decrease in the number of workers killed in vehicle crashes on public roads (68 down to 43).

The 191 fatalities in 2013 equates to a fatality rate of 1.64 fatalities per 100 000 workers. This is the lowest fatality rate since the series began 11 years ago. The highest fatality rate was recorded in 2004 (2.94).

Notable characteristics of worker fatalities in 2013 include:

- 176 of the 190 fatalities (92%) involved male workers. The fatality rate for male workers was 10 times the rate for female workers.

- Self-employed workers have much higher fatality rates than employees. In 2013, self-employed workers had a fatality rate of 4.39 fatalities per 100 000 self-employed workers, which was over three times the rate for employees of 1.32. The fatality rate for employees has fallen consistently over the past six years but there has been no improvement in the rate for self-employed workers. Perhaps highlighting the difficulties reaching small enterprises. Small enterprises often have limited resources to prioritise these risks and to improve the working environment, and they often have difficulties in complying with legislation.

- Fatality rates increased with age from 0.98 fatalities per 100 000 workers aged less than 25 years to 7.73 for workers aged 65 years and over. However if self-employed workers are removed then the fatality rate for older workers is substantially lower (4.56).

- Truck drivers accounted for 20% of worker fatalities over the past 11 years with 51 truck drivers killed on average each year. In 2013, 39 truck drivers were killed.

- Farm workers accounted for 18% of worker fatalities in 2013. This includes 24 farm managers and 11 farm labourers killed while working.

These are just some of the findings in the new Safe Work Australia report: Work-related traumatic injury fatalities, Australia 2013.

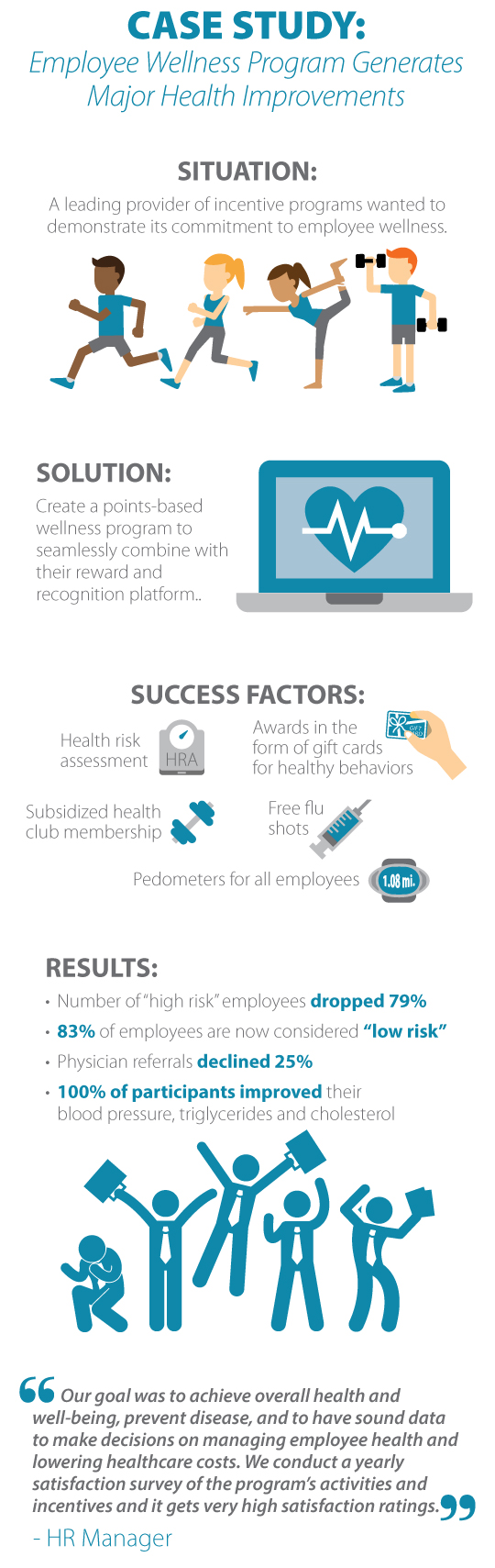

Infographic - Worksite Health Promotion Jul 14th, 2014

Workplace Walking Group - Worth the Effort?? Jul 13th, 2014

The combination of stress alongside sedentary behaviour is widespread in many workplaces. Therefore, workplace interventions specifically targeting sedentary behaviour and stress may help alleviate some of the risks for heart disease. Individuals who do not engage in regular physical activity (PA) have a 20–30% greater risk for heart disease, thus sedentary behaviour has been identified as a key health issue.

The combination of stress alongside sedentary behaviour is widespread in many workplaces. Therefore, workplace interventions specifically targeting sedentary behaviour and stress may help alleviate some of the risks for heart disease. Individuals who do not engage in regular physical activity (PA) have a 20–30% greater risk for heart disease, thus sedentary behaviour has been identified as a key health issue.The workplace is a suitable location for incorporating PA, such as walking, at a community level. Increasing activity during suitable periods of the day, such as lunchtime, provide opportunities for performing moderate activity and may, thus, break up long periods of sedentary time.

Current guidelines suggest that employers should encourage more active transport to and from work, more moving within the working day and promote walking during work breaks. Walking is eminently suited to population exercise prescription as it is easy to do, requires no special skills or facilities, and is achievable by virtually all age groups with little risk of injury.

The lunch break is often a time when employees continue to remain at their workstations due to work demands or peer-pressure from colleagues. Thus a detrimental cycle of increased stress and sedentary behaviour can prevail. The lunch period offers an opportunity to engage in moderate PA, interrupting long periods of sedentary time (i.e. prolonged sitting) and providing an opportunity to decrease stress levels and restore physical and mental fatigue.

The American College of Sports Medicine has adopted the recommendation that "every adult should accumulate 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity on most, preferably all, days of the week". However, compliance with these guidelines requires considerable commitment in terms of time spent exercising per week (≥ 150 minutes) and this may deter individuals from starting an exercise programme. There is some evidence that a training frequency of as low as two days per week may elicit improvements in cardio respiratory fitness in the lower fitness categories.

Murphy et al, 2006 evaluated the benefit of a progressive eight week workplace walking program. Participants walked twice per week for 45 minutes at a speed of their own choosing.

The results suggested self-paced walking 45 min, 2 days per week for eight weeks, reduces systolic BP and prevented an increase in body fat, in previously sedentary employees, and was associated with high adherence.

As there was little evidence this exercise intervention improved other markers of heart disease (Aerobic fitness, diastolic BP, body mass, cholesterol and other cardiac enzymes). This walking prescription may be useful as a stepping-stone to further increase levels of exercise in a previously sedentary workforce.

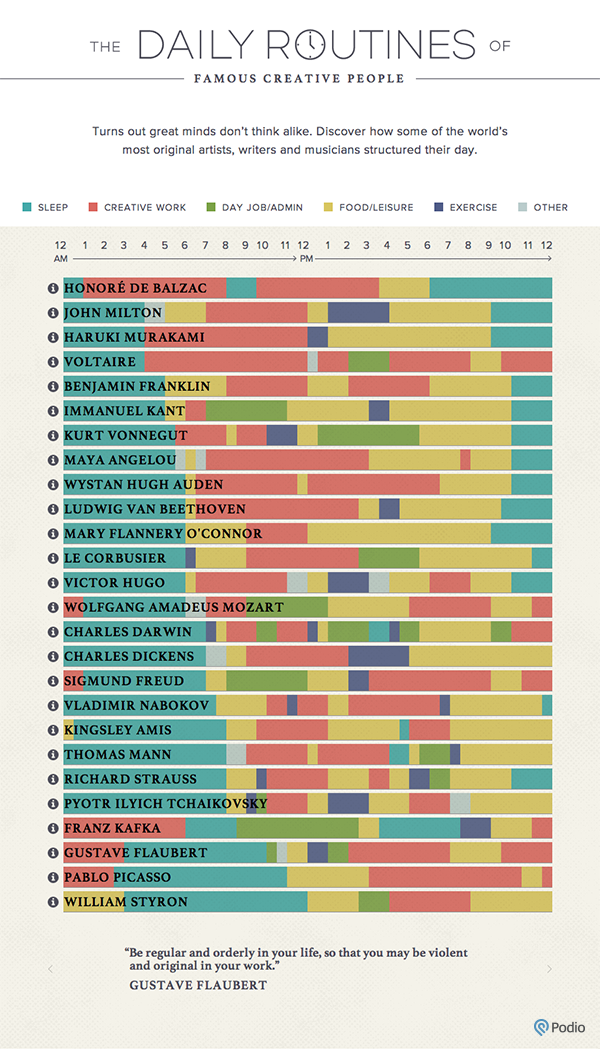

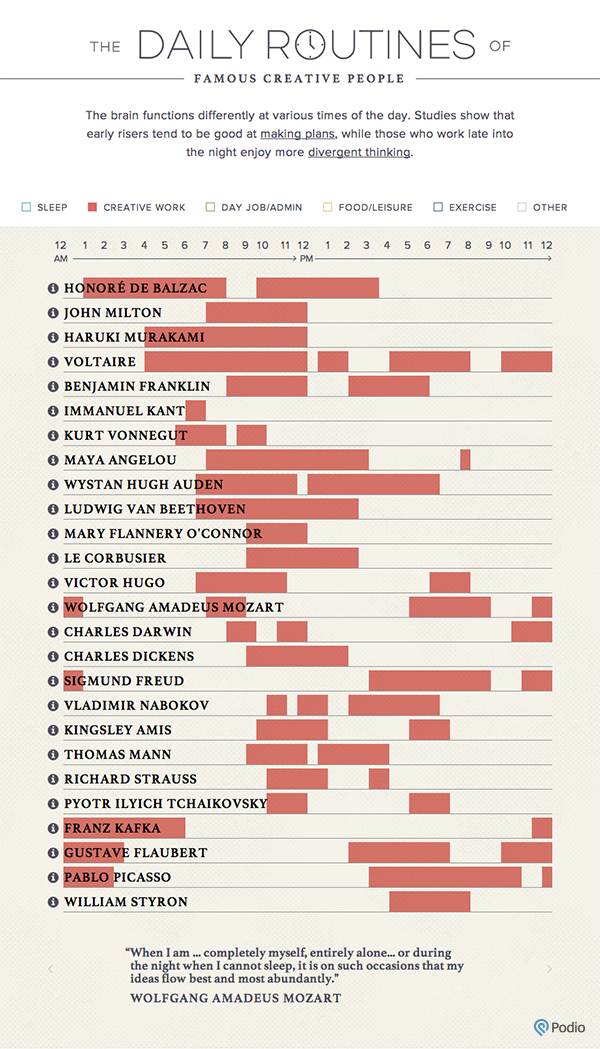

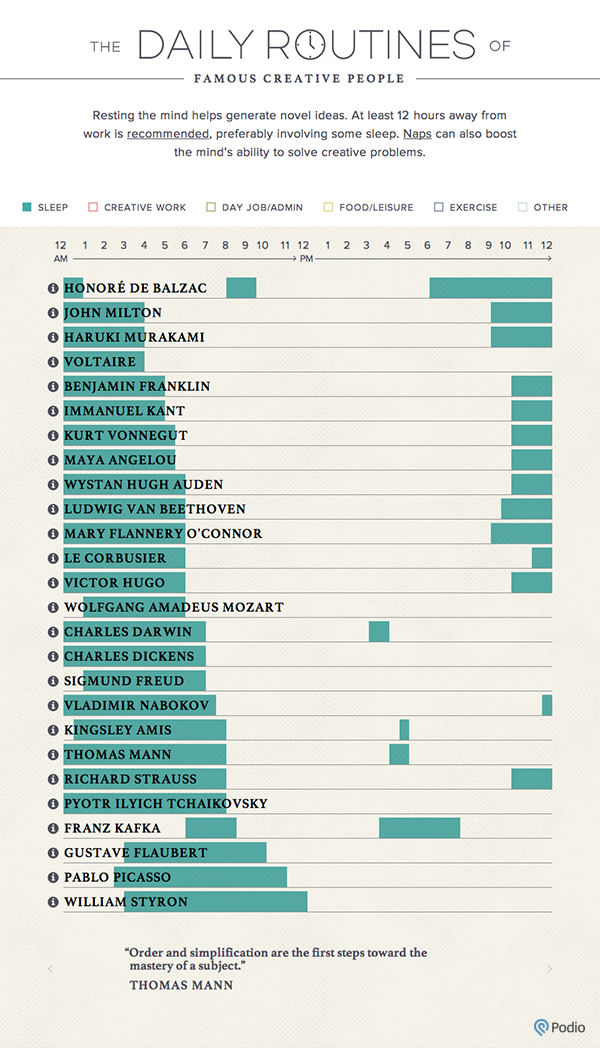

The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People Jul 11th, 2014

Image - The Priority Competency Model for Employee Supervisors Jul 9th, 2014

Media Release - Disadvantaged Australians Most at Risk of Obesity Jul 9th, 2014

Proof Exercise Changes Everything Jul 8th, 2014

The average adult needs at least two hours and 30 minutes of activity each week, if it's at a moderate intensity level, like brisk walking. Up the intensity to jogging or running, and you can aim for at least 75 minutes a week. Add in a couple of strengthening sessions a week, and you can expect to build muscle, protect your heart, avoid obesity and even live longer.

That's not to say that shorter bouts of exercise aren't worth it. Even just in 10-minute increments, exercise can make a marked difference in health and well-being. But those of us who make exercise part of their regular routine -- without overdoing it -- are certainly reaping the biggest benefits.

How much time do you spend sitting? Jul 7th, 2014

The mechanical risks of prolonged sitting in the workplace should not be overlooked Jul 5th, 2014

Low back pain (LBP) is an important public health problem in all industrialized countries. It remains the leading cause of disability in persons younger than 45 years and comprises approximately 40% of all compensation claims in the United States. More than one-quarter of the working population is affected by LBP each year, with a lifetime prevalence of 60–80%.

With the rapid development of modern technology, sitting has now become the most common posture in today’s workplace. Some three-quarters of all workers in industrialized countries have sedentary jobs that require sitting for long periods. Because of the reported link with LBP and the fact that in industrialized countries more of the population acquires a sedentary lifestyle, research examining sitting postures is becoming increasingly relevant (Dankaerts etal, 2006).

Among high risk occupational activities believed to increase low back pain, sitting is commonly cited as a risk factor along with heavy physical work, heavy or frequent lifting, non-neutral postures (i.e., trunk rotation, forward bending), pushing and pulling, and exposure to whole body vibration (WBV) (i.e., Truck driving, plant operation). It has been shown that intradiscal pressure is increased during sitting postures and prolonged static sitting postures are believed to have a negative effect on the nutrition of the intervertebral disc (Lis et al, 2006). Individuals who sit for extended periods can be at increased risk of injury if full flexion movements are attempted after sitting. This risk was evident after 1 hour of sitting, which could be of particular concern for those who design work–rest schedules and job-rotation schemes (Beach et al, 2005).

The above systematic review found the prevalence rate of reported LBP in those occupations that require the worker to sit for the majority of a working day is significantly higher than the prevalence rate of the general population. While the rate of LBP among occupations requiring extended periods of sitting was not quite as high as the rate of LBP among more strenuous occupations, it has been noted that the sitting group had the highest hospitalization rate for LBP (Lee et al, 2001). This suggests when low back injuries occur in people with sedentary occupations, these injuries tend to be more severe.

The risk of prolonged sitting in the workplace should not be overlooked and this risk appears to increase when coupled with whole body vibration (e.g truck driving or operating plant) and sustained awkward seating postures (e.g. lordosed or kyphosed, overly arched, or slouched).

Bovenzi and Betta compared a group of agricultural tractor drivers with a group of office workers. Both groups were exposed to static load due to prolonged sitting. However, only the tractor drivers group was exposed to the combined factors of WBV and awkward posture. They found that tractor drivers were 2.39 times more likely to report LBP than office workers.

Those people with chronic LBP (CLBP) often demonstrate difficulty in adopting a neutral midrange position of the lumbar spine. Furthermore, studies have described that during sitting CLBP patients often adopt such awkward seating postures potentially leading to abnormal tissue strain, pain and increased injury risk (Dankaerts etal, 2006).

At Central West Health and Rehabilitation our Small Business Injury Management Service includes gym memberships and conditioning sessions for workers who sit the majority of a working day.

Contact us for more

Preventing Shoulder and Neck pain in the Workplace Jul 5th, 2014

Neck and shoulder pain is a frequent health problem in employees. Globally, the annual prevalence has been estimated to range from 27.1 to 47.8 %. In general, acute neck pain resolves within days or weeks. However, neck pain may recur in 50–60 % of cases within 1 year, and for one in ten, neck pain may become a chronic condition. Thus, the identification of risk factors for neck/shoulder pain at the work place may be important in the prevention of recurrent and possibly chronic pain.

Neck and shoulder pain is a frequent health problem in employees. Globally, the annual prevalence has been estimated to range from 27.1 to 47.8 %. In general, acute neck pain resolves within days or weeks. However, neck pain may recur in 50–60 % of cases within 1 year, and for one in ten, neck pain may become a chronic condition. Thus, the identification of risk factors for neck/shoulder pain at the work place may be important in the prevention of recurrent and possibly chronic pain.The prevalence of neck/shoulder pain varies considerably across occupations. In addition to mechanical exposure, several psychosocial factors have been acknowledged as potential risk factors. The best documented mechanical risk factors is repetitive movement of the shoulder and neck flexion repetitive associated with repetitive work or precision work. Other mechanical factors like working with the hands above the shoulders, awkward postures, heavy lifting and manual handling have been discussed as possible risk factors, but the evidence is limited or inconclusive.

Several systematic reviews have designated high job demands and low social/work support as the most consistent psychosocial risk factors, whereas different aspects of job control (e.g. influence on the work situation) have been identified as potentially important but less consistent predictors of neck/shoulder pain

The aim of the above study was to determine work related psychosocial and mechanical factors that contribute to the risk of moderate to severe neck/shoulder pain. A significant relationship existed between both mechanical and psychosocial factors and the development of neck/shoulder pain in the general working population. Highly demanding jobs, neck flexion and awkward lifting appear as the most consistent and important predictors of neck/shoulder pain. Other significant work-related factors were low levels of supportive leadership, hand/arm repetition and working with the hands above shoulder.

Interventions aimed at reducing the development or return of neck/shoulder pain in the general working population may benefit from focusing on a range of both work-related mechanical and psychosocial factors.

Contact us for more.

Is Manual Handling Training Worth it? Jul 5th, 2014

Manual handling has been defined as any activity requiring the use of force exerted by a person to lift, lower, push, pull, carry, move, hold or restrain a person, animal or object. If these tasks are not carried out safely, there is a risk of injury and research shows a significant linkage between musculoskeletal injuries and manual handling, with the primary area of physiological and biomechanical concern being the lower back (Bernard et al, 1997).

Manual handling has been defined as any activity requiring the use of force exerted by a person to lift, lower, push, pull, carry, move, hold or restrain a person, animal or object. If these tasks are not carried out safely, there is a risk of injury and research shows a significant linkage between musculoskeletal injuries and manual handling, with the primary area of physiological and biomechanical concern being the lower back (Bernard et al, 1997).Only some 2% of individuals with back injuries who have been off work for more than 2 years will ever return to gainful employment. The loss of the ability to work can have a devastating consequence on not only the injured individual but also his or her entire family.

Measures to reduce risk of injury start with the requirement to avoid hazardous manual handling wherever practicable. Where this is not possible, attention should be given to the provision of lifting aids and task/workplace design. If a job cannot be ergonomically modified to be less physically demanding Pre-employment Physical Assessment is vital. It is important not to place individuals in a job for which they do not have the physical capabilities to perform.

The type of training offered and its effectiveness often depends on a multitude of factors such as method of teaching, organization setting and type of training technique that is used. However, concerns have been raised over the efficacy of current manual handling training methods (Dawson et al, 2007).