News

The mechanical risks of prolonged sitting in the workplace should not be overlooked Jul 5th, 2014

Low back pain (LBP) is an important public health problem in all industrialized countries. It remains the leading cause of disability in persons younger than 45 years and comprises approximately 40% of all compensation claims in the United States. More than one-quarter of the working population is affected by LBP each year, with a lifetime prevalence of 60–80%.

With the rapid development of modern technology, sitting has now become the most common posture in today’s workplace. Some three-quarters of all workers in industrialized countries have sedentary jobs that require sitting for long periods. Because of the reported link with LBP and the fact that in industrialized countries more of the population acquires a sedentary lifestyle, research examining sitting postures is becoming increasingly relevant (

Dankaerts etal, 2006).

Among high risk occupational activities believed to increase low back pain, sitting is commonly cited as a risk factor along with heavy physical work, heavy or frequent lifting, non-neutral postures (i.e., trunk rotation, forward bending), pushing and pulling, and exposure to whole body vibration (WBV) (i.e., Truck driving, plant operation). It has been shown that intradiscal pressure is increased during sitting postures and prolonged static sitting postures are believed to have a negative effect on the nutrition of the intervertebral disc (

Lis et al, 2006). Individuals who sit for extended periods can be at

increased risk of injury if full flexion movements are attempted after sitting. This risk was evident after 1 hour of sitting, which could be of particular concern for those who design work–rest schedules and job-rotation schemes (

Beach et al, 2005).

The above systematic review found the prevalence rate of reported LBP in those occupations that require the

worker to sit for the majority of a working day is significantly higher than the prevalence rate of the general population. While the rate of LBP among occupations requiring extended periods of sitting was not quite as high as the rate of LBP among more strenuous occupations, it has been noted that the sitting group had the highest hospitalization rate for LBP (

Lee et al, 2001). This suggests when low back injuries occur in people with sedentary occupations, these injuries tend to be more severe.

The risk of prolonged sitting in the workplace should not be overlooked and this risk appears to increase when coupled with whole body vibration (e.g truck driving or operating plant) and sustained awkward seating postures (e.g. lordosed or kyphosed, overly arched, or slouched).

Bovenzi and Betta compared a group of agricultural tractor drivers with a group of office workers. Both groups were exposed to static load due to prolonged sitting. However, only the tractor drivers group was exposed to the combined factors of WBV and awkward posture. They found that tractor drivers were 2.39 times more likely to report LBP than office workers.

Those people with

chronic LBP (CLBP) often demonstrate difficulty in adopting a neutral midrange position of the lumbar spine. Furthermore, studies have described that during sitting CLBP patients often adopt such awkward seating postures potentially leading to abnormal tissue strain, pain and increased injury risk (

Dankaerts etal, 2006).

Pre-Employment Physical - Cost Effective and Useful Jul 3rd, 2014

Pre-employment testing such as radiographic evaluations, physician administered physical exams, and lumbar range of motion, have generally been shown to be ineffective for injury prevention or injury prediction (

Jackson, 1994). Strength testing when correlated to job specific tasks has shown a correlation to work-related injuries. Individuals lacking the physical capabilities to work at the level that their job physically required had a significantly increased incidence of low back injuries.

Controlling the incidence of work-related injuries is economically important for industry, but is of far more importance for the individual employee. Injuries occurring on the job can result in life-altering consequences to workers who depend on their physical well being for their livelihood. Only 2% of individuals with back injuries who have been off work for more than 2 years will ever return to gainful employment. The loss of the ability to work can have a devastating consequence on not only the injured individual but also his or her entire family.

The most efficient methods of controlling workmen’s compensation expenses are geared toward lowering the rate of injury. Several authors have demonstrated that jobs requiring heavier lifting result in a higher incidence of low back pain. One method of

controlling work injury rates is to ergonomically re-engineer jobs to be less physically demanding. This approach creates a safer, less physically stressful work environment that benefits the employee. If a job cannot be

ergonomically modified to be less physically demanding, it becomes a safety issue to place individuals in a job for which they do not have the physical capabilities to perform.

Aiming to identify and monitor any functioning or health abnormality in prospective employees, pre-employment medical examinations traditionally rely on the classic assessment of specific medical conditions or substance abuse. However, this is not particularly relevant for fitness-for-work decisions. The assessment of fitness for work related to physical and mental job demands seem a better predictor than searching for a medical diagnosis.

There is strong evidence of an association of occupational injury occurrence and certain personal and non-occupational risk factors. In industry, effective injury reduction programs should go beyond traditional methods of job-related ergonomic risk factors and include personal factors such as smoking, weight control, and alcohol abuse (

Craig et al, 2006).

As well as highlighting candidate suitability, pre-employment physical assessments (PEPA's) with a trusted service provider provide a number of other important benefits:

- PEPA's provide a mechanism that can be tightened or loosened according to the employment environment.

- PEPA's provide a great place for manual handling education and training for injury prevention advice.

- PEPA's provide a great place to highlight and commence worksite health promotion for high risk employees.

- PEPA's can be used to negotiate a reduction in your insurance premiums when discussing your yearly insurance premiums with insurers.

Central West Health and Rehabilitation has significant experience in designing and providing Cost Effective Pre-employment Physical Assessments. Contact us for more

Video - Central West Health and Rehabilitation Jul 3rd, 2014

Alcohol: Impact on Sports Performance and Recovery Jul 1st, 2014

Above the safe levels recommended by the WHO, alcohol consumption becomes hazardous (4–6 or 2–4 standard drinks per day for males and females, respectively). Even larger amounts are classified as harmful and may significantly increase the risk.

In addition to hazardous, chronic alcohol consumption, heavy acute episodic or binge drinking, classified as the consumption of 60g of alcohol in a single drinking episode, is associated with significant physical, psychological and social harm. Approximately 16.5 % of the world’s population are thought to participate in heavy episodic drinking on a weekly basis of negative mental and physical health issues, such as a range of cancers, hypertension, stroke and injuries related to violence.

While acute and chronic misuse of alcohol is common place in the general population, the athletic/sporting population is not exempt from such behaviour. Athletes often do not consider alcohol as harmful in the same way they consider other recreational drugs. Therefore it is important athletes have a full understanding of the implications alcohol consumption may have on sporting performance, recovery and, perhaps more importantly, general health.

The most relevant point is how the consumption of alcohol after exercise alters recovery and adaptation. Dehydration has been shown to impair performance and so adequate rehydration and restoration of electrolytes after exercise is important to ensure recovery before the next training session or event. It has been suggested that the best opportunity for optimising glycogen stores occurs when carbohydrate is consumed in the initial hours after exercise; after that time, glycogen storage rates decrease significantly.

However, in many sports this period after competition may be spent consuming alcohol instead of following correct nutritional strategies. Small volumes of alcohol, at a dose less than 0.49 g/kg Body Weight, after exercise without negatively impacting rehydration, however, if fluid replacement is not a priority, for example if optimal performance is not required the next day, then the consumption of alcohol post-exercise in larger volumes may be acceptable, at least from a hydration stand point.

Particularly important for males, in both athletic and general populations, is the reduced production of testosterone and subsequent effects on body composition, protein synthesis and muscular adaptation/regeneration; these effects are likely to inhibit recovery and adaptation to exercise. Low doses of alcohol, post-exercise are unlikely to be detrimental to repletion of glycogen, rehydration and muscle injury; however, the effects of alcohol are dependent on the timing of consumption, nutritional status and the priority given to optimal rates of recovery. Higher doses should be avoided if injury to skeletal muscle has occurred. While very high, hazardous doses of alcohol consumed after strenuous exercise may not directly impact performance in the days after exercise, such bingeing behaviour is associated with long-term physical, psychological and social harm and should therefore be avoided.

It should be remembered that alcohol is a poison and as such should be treated as one!

While less likely to occur than drinking large volumes of alcohol after sports, the consumption of even low doses of alcohol prior to athletic endeavour should be discouraged due to negative effects of alcohol on endurance performance.

Health Related interventions for Shift Workers Jul 1st, 2014

Shift work is prevalent in healthcare, emergency services, manufacturing, retail, and hospitality. Some jobs require regular work on the same night shift (ie, permanent night shift), while others are employed on rotating shift schedules involving days and nights.

Shift work, particularly work at night, has been found to disrupt endogenous circadian rhythms involved in melatonin expression, sleep patterns, food digestion, and other physiological processes. Work at night is associated with a range of known and potential adverse health effects.

Aside from potential cancer risks, shift workers also experience increased incidence of chronic illnesses including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (a combination of obesity, dyslipidemia, high cholesterol, and insulin resistance), as well as gastrointestinal disorders, workplace injuries, and disruption of family and social life.

The short- and long-term effects of shift work on sleep have also been studied. Night work has been shown to reduce sleep quantity and quality on workdays and days off. While shift workers tend to fall asleep rapidly in the morning immediately following a night shift, sleep tends to be shorter due to the natural awakening effects of circadian rhythms during the daytime, as well as social cues and daytime commitments. Sleep questionnaires completed by shift workers show reduced sleep length and higher frequencies of sleep difficulties, intermittent sleep, and early waking. Poor sleep quality and quantity have been shown to be related to various chronic diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. Thus, sleep quantity and quality are important outcomes of interventions aimed at improving long-term health among shift workers.

There is a need for interventions that can be implemented in workplaces – or by workers outside of work hours – to mitigate the harmful effects of shift work. The main objective of this review was to synthesize intervention studies designed to mitigate the adverse health effects of shift work.

Controlled light exposure

The aim of interventions that control light exposure is to shift circadian rhythms and subsequently promote adaptation to work at night, thereby minimizing health effects. A combination of timed bright light and light-blocking goggles appeared to promote adaptation to shift work as primarily measured by changes in sleep and melatonin. Timed exposure to high intensity light during night shifts and wearing goggles during the commute home can increase circadian adaptation. Multi-pronged interventions to control light exposure may be more effective than using bright light or light-blocking goggles alone. Adverse events for bright light exposure were headaches or feelings of heat/cold in response.

Shift schedule change

Fast-forward rotating shifts tended to report more favourable results for sleep. However, findings were inconsistent for changes in shift length or start time. Shift workers may be less likely to engage in regular physical activity, smoking cessation, and healthy diet, which may contribute to increased risks of adverse health outcomes. Objective outcomes that may be the result of improved lifestyle habits, such as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; triglycerides, fasting glucose, and blood pressure; cardiorespiratory fitness; and blood pressure, did show improvement in association with a change in shift schedule.

Interventions directed at physical activity and weight loss improved cardiorespiratory fitness and strength, body composition, blood pressure, and physical activity. This suggests that lifestyle habits may not improve spontaneously among shift workers as a result of shift schedule changes, and interventions specifically targeted at improving lifestyle behaviours may be necessary. Adverse effects were difficulty scheduling social or family activities as a result of a shift schedule change.

Behavioural interventions

Physical activity improved sleep length with variable results on subjective sleep quality, and education about sleep hygiene strategies resulted in significantly improved REM sleep time. A 1-hour rest period during the night resulted in no significant change in sleep duration following the night shift. Other outcomes were also evaluated. Exercise significantly increased maximal aerobic capacity and strength, although circadian phase did not differ between groups, as measured by body temperature. A group based lifestyle intervention for weight loss was associated with significantly decreased body mass index and blood pressure and significantly improved physical activity and fruit intake.

Pharmacological interventions

Studies of melatonin, hypnotics, and stimulants showed mixed results, potentially due to different doses administered to workers, compliance, shift schedule variation, and other factors. Administration of Modafinil did not significantly change endogenous melatonin levels or sleep quantity before or after night shifts. Armodafinil resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in nighttime sleep latency but had no effect on daytime sleep. Some adverse effects were reported, including insomnia and headache from Modafinil, and nausea, anxiety, low-back pain, and other effects from Armodafinil.

Conclusions

Comprehensive, evidence-based approaches that include best practices in shift scheduling, a range of options to control exposure to light and dark, support for physical activity and healthy eating, as well as pharmacological agents, may be the best ways to improve health. There is also a need to develop and test novel approaches, like social support, possibly using new technologies such as smart phones to help with sleep or other adverse effects. There is no “one size fits all” solution, and individual shift workers may have different responses to interventions as the result of chronobiology, personal preferences that affect compliance, or other factors that remain to be assessed.

Fruit juice: just another sugary drink Jun 30th, 2014

The evidence for a role of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in the development of obesity and associated comorbidities, is becoming increasingly convincing.

Liquids have a smaller satiating effect than do solid foods, and consequently excess calories consumed in liquid form are not fully compensated for by reduction of intake of other foods. Evidence exists that non-alcoholic beverages contribute a substantial proportion of daily sugar intake (about a quarter of sugar intake in the UK), are consumed separately from other dietary components, are of little nutritional benefit, and that alternatives in the form of low-sugar drinks and water are readily available.

By contrast with the growing consensus to limit SSB intake, consumption of fruit is regarded as virtuous, with WHO guidelines recommending consumption of fruit and vegetables—eg, in the UK, the guidelines recommend five servings per day, and one of these portions can be in the form of fruit juice.

However, fruit juice has a similar energy density and sugar content to SSBs: 250 ml of apple juice typically contains 110 kcal and 26 g of sugar; 250ml of cola typically contains 105 kcal and 26·5 g of sugar. Additionally, by contrast with the evidence for solid fruit intake, for which high consumption is generally associated with reduced or neutral risk of diabetes, high fruit juice intake is associated with increased risk of diabetes.

In the modern context, where society is faced with an energy surfeit, health-care providers and policy makers must take every opportunity to help individuals to cut unnecessary calories from their diet. Some go as far as suggesting that fruit juices are sugary drinks and should be taxed and/or recommend elimination of all fruit juice consumption from children’s diets.

While extreme, this does highlight that the debate about the SSB reduction should include fruit juice.

Lifting Strategies of Expert and Novice Workers Jun 28th, 2014

Manual material handling (MMH) involves considerable physical work demands and is considered a high-risk task for low back pain (LBP). The risk increases with the magnitude of the physical exposure in terms of the load moment, trunk motion dynamics and trunk posture. There exists a large variability in low back loading and lifting posture that could be explained by individual differences (between subjects) and by trial-to-trial variations. Thus, for the same task, spine loading and posture can change markedly between trials and individuals.

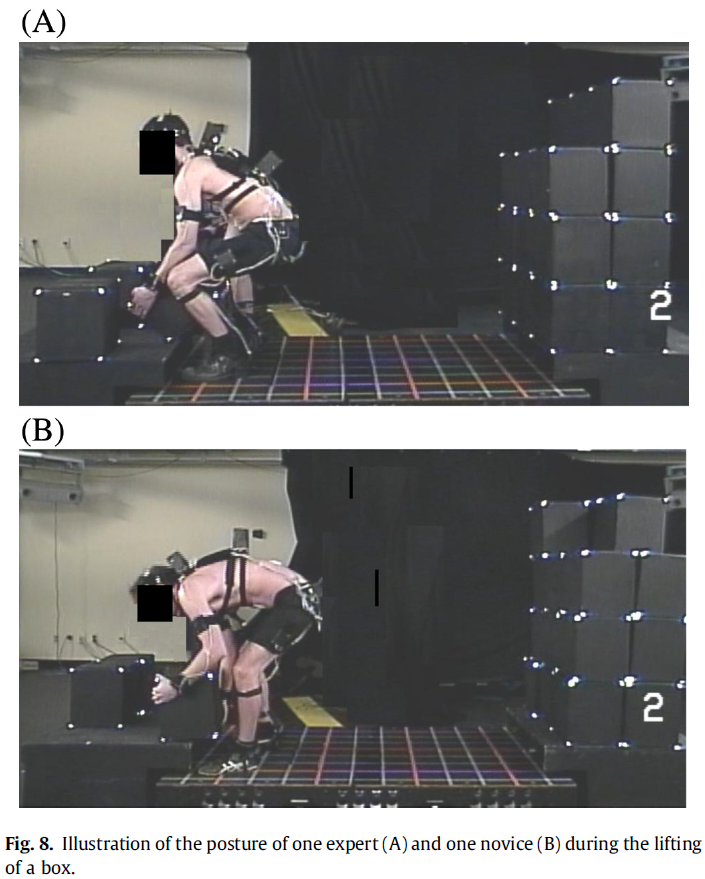

The above study showed that 'expert' workers differed from novices mostly in the posture-related variables (lumbar flexion angle, trunk inclination, knee flexion) and much less in the back loading ones (peak resultant moment or asymmetrical moment at L5/S1). Experts posture was quite different from the novices at the instant of the peak resultant moment as they bent their trunk and lumbar region less (even when age was accounted for with the lumbar flexibility index). Moreover, their knees were more flexed when the box was lifted from the floor of the pallet. Experts were also closer to the box during both the lifting and the deposit phases (

See Image).

These posture-related variables could have a major impact on the distribution of internal forces on the spine, but expertise had a very small effect on the external back loading variables (peak resultant moment and peak asymmetrical moment at L5/S1), which are important indicators of risk in terms of work-related back injuries.

Various intervention strategies, such as training employees in safe lifting techniques, are used with the aim of protecting workers from back injuries. Recent reviews have seriously questioned the effectiveness of training programs as a mean of reducing back injuries. However, these reviews are based on a small number of studies, and the quality of the training intervention is generally not questioned. Important aspects such as the content of the training course, its duration and its specificity to the work context are worth consideration.

A simple question that still needs to be answered is “What should be taught?”.

Manual handling training is generally given over a very short time; as a result, the “training” is really more of an information session. When training is specific to the task and dispensed over a longer timeframe, a decrease in back loading and back injuries is possible (

Schibye et al., 2003). The following study suggests ergonomic intervention with the aim of reducing

external back loading should primarily focus on

major factors such as the load height and horizontal distance between the lumbar spine and the load lifted in order to reduce the external back moment, and not just on workers’ technique.

Image - Expert and novice Lifting Jun 28th, 2014

Video - Incorrect Vs Correct Lifting Jun 28th, 2014

External Assistance for Injury Management Systems Jun 27th, 2014

Western Australia is fortunate to have an insurance premium-related incentive scheme where a company’s insurance premium is graded according to claim experience. However, smaller enterprises often have difficulty making use of the benefits.

National Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) intervention programmes are often difficult to implement in smaller enterprises. Despite it being generally accepted that small enterprises with less than 50 employees have higher exposure to occupational hazards than larger organisations, smaller enterprises often have limited resources to prioritise risks and to improve the working environment, and they often have difficulties in complying with legislation.

The Western Australian workers’ compensation system requires every employer to:

1) Have workers’ compensation cover for all workers (penalties apply for avoidance).

2) Have a documented Injury Management System outlining the steps taken when a worker is injured and contact details of person responsible for the Injury Management System.

3) Establish and implement a Return to Work Program as soon as practicable after:

- the treating doctor indicates in writing the need for a Return to Work Program; or

- the worker’s treating doctor signs a medical certificate to the effect that the worker has partial capacity for work or has total capacity for work but is unable to return to their pre-injury position for some reason.

Small enterprises constitute a major challenge for efforts to improve occupational injury management as they, on one hand, have extensive needs, and on the other hand, are difficult to reach. At particular stages in a businesses development there is legitimate grounds, both personal and financial, for sourcing an external service provider to assist with the injury management and injury management system development.

Costs of Going it Alone:

1) Time to Research a System $$/hour

2) Time to design a system $$/hour

3) Time for Template Design $$/hour

4) Costs of employing Injury Management Co-ordinator $$/hour

Central West Health and Rehabilitation offer a ‘low cost’ Injury Management Service specifically designed for Small Businesses not yet ready to employ specific Injury Management Staff.

The role of client motivation in Return to Work Jun 26th, 2014

To reach the desired return to work outcome, the Rehabilitation Counsellor is required to identify social, economic, and environmental factors that may adversely affect a client’s motivation toward rehabilitation. Motivation has been recognised as an essential component in managing medical issues, adjusting to physical disability, cognitive impairment, returning to work, and improving psychosocial functioning.

It is too simplistic to say people are motivated or not; rather people are motivated by different things and this can be influenced. Motivation refers to the underlying internal and external influences on behaviour that determine whether a person will achieve the desired rehabilitation goals.

The current article focuses on understanding the concept of motivation, reasons for its presence or absence, and why motivation is important to the workplace rehabilitation process. The authors also explore significant influencing factors that may be utilised to increase motivation and promote more successful return to work outcomes.

Immediately after the onset of work disability/injury, the return to work aspect of rehabilitation may not be a priority; however as the rehabilitation and return to work process develops, priorities change and motivations to reach personal goals are highlighted. Motivation does not become a focus at any one point in the rehabilitation process, but rather should be maintained throughout the return to work process. Positive and lasting results most likely occur when a client becomes motivated, actively engaged, and invested in change in all aspects of their life.

Factors that Influence Motivation

- Internal motivation- the willingness, readiness, and desire to change to achieve the desired outcome

- Key stakeholders- It is important that all stakeholders have the potential to gain from the worker successfully returning to work to ensure each stakeholder has an interest in motivating the client to strive for the return to work outcome

- Social supports- strong network of good relationships.

- External regulation- Pressure from third party payers in many settings dictates a short-term and limited funding approach to change, which makes motivation more critical. It also makes motivation more difficult to establish as clients have less control.

- Perceived costs and benefits- the client might be more willing to participate in the rehabilitation process if they are able to see the benefits and payoffs in the future. Possible costs within a workplace rehabilitation plan include the required effort to participate fully, as well as the associated tiredness or pain.

- Hope and individual beliefs surrounding working identity- People have increased motivation to return to work if their job is meaningful and they have a sense of belonging and being appreciated.

GP and patient predictions of sick-days duration Jun 25th, 2014

In general practice, sick-listing (give days off work) is a frequent and cost-generating measure often experienced as problematic for the doctor. One reason is that sick-listing involves assessment of how the symptoms reduce the patient’s ability to work, requiring physicians to rely on the patient’s own description of the job and his/her capacity to do it. From the patient’s point of view, the sick note is important if his/her self-perceived ability to work is low. Without the note the patient must keep on working, and patients often worry that working may affect their health negatively. Thus, consultations involving sick-listing assessment involve several difficult considerations on the part of both the physician andthe patient.

In this study the correspondence between the patients’ and the GPs’ perception of the duration of sick-listing was not high. Furthermore, the correspondence between the patients’ and GPs’ respective predictions of sick-listing duration, made at the first consultation, and the respective actual duration was rather low.

Implications

Many other factors besides the employee's medical conditions– e.g. organizational, work-environmental, and social. These factors might be hard to take into consideration at the first consultation, and might not become evident until after several visits. Early in the process, medical factors might be more important for both the physician and the patient, and only a brief consultation may be made regarding workplace factors. This seems to be a relevant approach; however, being sick-listed might in itself influence the patient ’ s motivation and confidence in returning to work. It is important to address issues related to occupation and the workplace early in the consultation to support the process of returning to work efficiently.

This can be assisted by the Injury Management Co-ordinator attending initital medical appointments, or providing your employees a preferred medical providerIn the present study, the overall correspondence between the GPs ’ prediction of the interval until return to work and the actual duration of sick-listing was not high on the whole. It is possible that the patients ’ expectations might have affected the interval until their return to work.

Patient expectations and a focus on return to work is important to promote from the first medical appointment.

Poor nutrition leads to development of chronic diseases Jun 24th, 2014

International research involving the University of Adelaide has shown for the first time that poor nutrition – including a lack of fruit, vegetables and whole grains – is associated with the development of multiple chronic diseases over time.

The results of the study, which looked at health, diet and lifestyle data of more than 1000 Chinese people over a five-year period, are published in this month's issue of the journal Clinical Nutrition.

Study co-author Dr Zumin Shi, from the University of Adelaide's School of Medicine suggested "Those participants who ate more fresh fruit and vegetables, and more grains other than wheat and rice, had better health outcomes overall. Grains other than rice and wheat – such as oats, corn, sorghum, rye, barley, millet and quinoa – are less likely to be refined and are therefore likely to contain more dietary fibre. The benefits of whole grains are well known and include a reduction in cardiovascular disease, diabetes and colorectal cancer."

Video - Dietitian Summary Jun 23rd, 2014

Video - Fat Vs Sugar Jun 23rd, 2014

Video - What is Diabetes Jun 22nd, 2014

Video - Energy Balance and Weight Loss Jun 22nd, 2014

Video - Exercise and Chronic Disease Jun 22nd, 2014

Video - Behaviour Change and New Years Resolutions Jun 22nd, 2014

Rationale for using an intermediary to assist small businesses with Injury Management Systems Jun 22nd, 2014

It is generally accepted that small enterprises with less than 50 employees have higher exposure to occupational hazards than larger organisations. Small enterprises often have limited resources to prioritise these risks and to improve the working environment, and they often have difficulties in complying with legislation. Small enterprises constitute a major challenge for the society’s effort to improve occupational injury management as they, on one hand, have extensive needs, and on the other hand, are difficult to reach. Just one worksite injury could produce serious economic consequences to a unprepared small business.

Hasle and Limborg have developed a model for reaching out to small enterprises with intervention programmes. The model emphasises the need for inclusion of not only the concrete changes of the working environment but also the process in which small enterprises are approached and motivated to start a change process.

The model can be used to construct a stepwise procedure for the design of working environment programmes. The idea is to start from the right side of the model and subsequently work backwards through the chain in order to end up with a full designed programme. The design procedure therefore has five steps:

- Defining the OHS challenges of the target group (health outcome).

- Selecting methods and solutions that can improve the working environment by reducing the exposure and thereby producing the intended health outcome (improvement of the working environment).

- Developing theories about mechanisms which can motivate the target group to initiate change. On the general level, there are three main mechanisms: regulation, incentives, and information (change process).

- Analysing how the specific context of the target group may influence motivation and implementation of the intervention (context).

- Designing the programme which builds on the results of the four preceding steps (programme).

This method has been used in the development of a practical intervention programme aimed at

small construction enterprises. The transparency opens the possibility for critical discussions and thereby improvements of both design criteria and design conclusions.

Fatal accidents in the Western Australian mining industry 2000-2012 Jun 21st, 2014

This report examines the 52 fatal mining accidents that occurred in Western Australia over the 13-year period from 2000 to 2012, inclusive. The information was analysed to identify common hazards, causation factors and critical activities.

Twenty-four causation factors were identified and used to provide a framework for analysis. A person might conduct 50 to 100 tasks during a shift, of which just one or two could lead to a situation with the potential for serious injury or death. So knowledge of the critical tasks is important when addressing risks.

Factors for which trends or clusters were identified were:

- Occupation of deceased

- Duration in the role

- Duration at the mine site

- Supervisors Duration in the role

- Compliance with procedures

- Trigger events

- Time of day

- Surface or underground

- Commodity group

- Original equipment manufacturers’ procedures

- Age of deceased

- Roster cycles

These factors are discussed in more detail in the relevant document along with significance of trigger events to individual fatalities and critical activities.

Strategies to Help Employees Return to Work Jun 21st, 2014

Engaged and productive employees are the lifeblood of almost every business. No employer wants valuable human resources at home when they could be working. Time off work is unhealthy. The longer an employee is off work the less chance there is of returning to work (

RTW).

The World Health Organization for example, stated in an international study that safe and productive work is a major source of physical and psychological well-being.

Does your workplace currently have an Injury Management System as required by Workcover WA? Are you seeing the results that you expected to see? Maybe your workplace is fully insured or you are trying to manage your benefit programs in-house, or as part of duties of the HR Department. Have you become overburdened with administration and less than satisfactory results?

The key components of an Injury Management System should include:

Senior support

One of the foundations of a solid injury management is to get

senior support on side. The challenge of managing disability in both human and financial terms is enormous, yet the factors involved in finding the right strategy are still poorly understood at an organizational level. There are many reasons to get an organisation interested in injury management.

Early Identification

Injury Management Systems begin with

early identification of injuried workers. Also crucial is the identification of potential conditions that can result in worker disability.

The sooner there are the correctly identified symptoms the sooner return to work planning can put in place strategies to resolve them. Early intervention is proactive and affords the opportunity to identify which claims may need special handling to resolve them early.

Evaluation of medical, psychosocial and return to work needs.

We have found three types of disability groups have come to light over the years.

GROUP 1

The first is short duration claim where the patient has a well-defined acute episode (i.e. flu, strain or sprain). These cases will return to work often with minimal intervention.

GROUP 2

The second group represents patients with sub-acute or progressive diseases or injuries. This population often needs help with ensuring the primary interventions are enough to progress back to health. They may need help in finding their way through the health care maze to a provider that can assist in resolving their medical or psychosocial issues. It is important to keep this group focused on the return to work goal and that may need assistance via a graduate RTW.

GROUP 3

The third group are those with terminal or debilitating diseases, such as Chronic Pain, Cancer or Multiple Sclerosis, that may eventually prevent return to work. The primary needs are ensuring these people are familiar with the range of services available in their community and providing help with ongoing discussions on their level of ability.

Ability Management

In all three groups, there are essential best practices to bear in mind.

Focus on what the person can do, not the cure. If disability limits what a person can do due to illness, injury or a condition then effective management, rather than eliminating symptoms, discusses what the employee is able to do.

Symptoms such as pain are not disability, they are symptoms. Often staying at home and dwelling on the pain can lead to a

Chronic Pain Syndrome. Work provides many people with friends, support networks, focus, meaning and distraction from ruminating on a condition.

Focus on ability is the goal, while being compassionate but firm. It is important to work together and empathize with the conflicting feelings of pain versus disability; however, through gradual transition back to work the symptoms will decrease as the tolerance for activity or interaction increases.

Return to Work

Return to work should always be the goal.

From the first interaction with the employee, their physician, their manager, and/or the union representative (where applicable) make it clear that any treatment, medication, protocol or intervention is for returning the employee to work as soon as possible. Encourage health care providers to set up tentative return to work dates.

Discuss the appropriate treatment duration. For example, with a back injury, emphasize that a few days bed rest, active physiotherapy, rapid reactivation, and return to normal activity levels, is the general strategy for most people.

In this situation, it is also necessary to emphasize that returning to work is not about waiting for the absence of pain. What the employee is able to do, not pain, is the benchmark for returning to work.

Reasonable job accommodations or transitional jobs (i.e.

suitable duties) are a necessary part of effective return to work. An effective return to work program often includes a phase in which the employee returns for specified periods and specific tasks. The intent should always be a return to a regular position. This could be either the pre-disability position – or another suited to the employee’s skills, capabilities and knowledge. Alternative duties should be re assessed regularly.

Measurement of the results

An effective injury management program needs to have a way to measure its outcomes.

Comparison of data from one period to the next is critical to measure the effectiveness of a particular intervention. When the goals set for the system are measurable it helps to determine their effectiveness. In the end you are able to say, “what was it before and how are we doing now.”

As well as gathering the data, there is the need to communicate the results and use them to drive

prevention programs. When you get all parties involved to embrace the broader view of disability management it can be a very effective part of taking care of your business.

Video - Understanding Chronic Pain Jun 21st, 2014

Returning to work – a long-term process reaching beyond the time frames of multimodal non-specific back pain rehabilitation Jun 21st, 2014

Low Back pain (LBP) is a common health problem. Furthermore, long-term back pain often exerts a negative impact on participation in everyday activities. Health professionals strongly emphasise the importance of focusing rehabilitation on aspects that improve the patient’s well-being and quality of life. Return To Work (

RTW) might then be a possible, but not a necessary, feature of LBP rehabilitation. This is one explanation for the modest effect rehabilitation has exerted on reduced sickness absence.

Previous research has found that focusing on the patient’s everyday life is important in efforts aimed at reducing sickness absenteeism and in increasing RTW as well-functioning everyday life can promote RTW. Still, other research has shown that patients may also experience uncertainty about how to proceed with the process of RTWafter rehabilitation is completed, particularly when there has not been a clear connection between features in the rehabilitation and the patients’ work situations. Furthermore, interventions that included structured meetings of employee, employer and health professional, that took up planning and agreements regarding suitable work modifications, appeared to be more effective in the promotion of RTW in people with back pain on long-term sick leave than the interventions that do not include these features. This is despite significant research highlighting the

health benefits of work.

In the above study, Fifteen participants were interviewed, all were working with multimodal rehabilitation for people with non-specific back pain in eight different rehabilitation units. The participants experienced RTW as a long-term process reaching beyond the time frames of the medical rehabilitation. Their attitudes and, their patients’ condition, impacted on their work which focused on psychological and physical well-being as well as participation in everyday life. Health professionals often created an action plan for the RTW process, however the responsibility for its realisation was often transferred to others (i.e. the patient). The participants described limited interventions in connection with patients’ workplaces.

Implications

Rehabilitation programs targeting return to work (RTW) for people with non-specific back pain needs to include features concretely focusing on vocational issues.

�Health and RTW is often seen as a linear process in which health comes before RTW. Rehabilitation programs could be tailored to better address the reciprocal relationship between health and work, in which they are interconnected and affect each other.

The RTW process is reaching beyond the time frames of the multimodal rehabilitation but further support from the patients are asked for. The rehabilitation programs needs to be designed to provide long-term follow-up in relation to the patients’ work.

Time to Move on Physical Activity as Usual Care for Mental Illness Jun 18th, 2014

Physical inactivity is estimated to cause 9% of premature mortality worldwide, but recognition of the benefits of being physically active is increasing. In addition to the cardiometabolic benefits of regular bodily movement, physical activity has repeatedly been shown to have antidepressant and anxiolytic qualities, both as monotherapy and as adjunctive therapy. At what point do we decide that sufficient evidence exists for a cultural change within psychiatric care, whereby exercise physiologists or physical therapists (and indeed dietitians) are considered as standard members of the multidisciplinary mental health team?

Simon Rosenbaum, BSc from the The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia gives us some good reasons why in this blog post:

Time to Move on Physical Activity as Usual Care for Mental Illness

Pre-employment testing such as radiographic evaluations, physician administered physical exams, and lumbar range of motion, have generally been shown to be ineffective for injury prevention or injury prediction (Jackson, 1994). Strength testing when correlated to job specific tasks has shown a correlation to work-related injuries. Individuals lacking the physical capabilities to work at the level that their job physically required had a significantly increased incidence of low back injuries.

Pre-employment testing such as radiographic evaluations, physician administered physical exams, and lumbar range of motion, have generally been shown to be ineffective for injury prevention or injury prediction (Jackson, 1994). Strength testing when correlated to job specific tasks has shown a correlation to work-related injuries. Individuals lacking the physical capabilities to work at the level that their job physically required had a significantly increased incidence of low back injuries. As well as highlighting candidate suitability, pre-employment physical assessments (PEPA's) with a trusted service provider provide a number of other important benefits:

As well as highlighting candidate suitability, pre-employment physical assessments (PEPA's) with a trusted service provider provide a number of other important benefits: Particularly important for males, in both athletic and general populations, is the reduced production of testosterone and subsequent effects on body composition, protein synthesis and muscular adaptation/regeneration; these effects are likely to inhibit recovery and adaptation to exercise. Low doses of alcohol, post-exercise are unlikely to be detrimental to repletion of glycogen, rehydration and muscle injury; however, the effects of alcohol are dependent on the timing of consumption, nutritional status and the priority given to optimal rates of recovery. Higher doses should be avoided if injury to skeletal muscle has occurred. While very high, hazardous doses of alcohol consumed after strenuous exercise may not directly impact performance in the days after exercise, such bingeing behaviour is associated with long-term physical, psychological and social harm and should therefore be avoided.

Particularly important for males, in both athletic and general populations, is the reduced production of testosterone and subsequent effects on body composition, protein synthesis and muscular adaptation/regeneration; these effects are likely to inhibit recovery and adaptation to exercise. Low doses of alcohol, post-exercise are unlikely to be detrimental to repletion of glycogen, rehydration and muscle injury; however, the effects of alcohol are dependent on the timing of consumption, nutritional status and the priority given to optimal rates of recovery. Higher doses should be avoided if injury to skeletal muscle has occurred. While very high, hazardous doses of alcohol consumed after strenuous exercise may not directly impact performance in the days after exercise, such bingeing behaviour is associated with long-term physical, psychological and social harm and should therefore be avoided. Shift work is prevalent in healthcare, emergency services, manufacturing, retail, and hospitality. Some jobs require regular work on the same night shift (ie, permanent night shift), while others are employed on rotating shift schedules involving days and nights.

Shift work is prevalent in healthcare, emergency services, manufacturing, retail, and hospitality. Some jobs require regular work on the same night shift (ie, permanent night shift), while others are employed on rotating shift schedules involving days and nights. National Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) intervention programmes are often difficult to implement in smaller enterprises. Despite it being generally accepted that small enterprises with less than 50 employees have higher exposure to occupational hazards than larger organisations, smaller enterprises often have limited resources to prioritise risks and to improve the working environment, and they often have difficulties in complying with legislation.

National Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) intervention programmes are often difficult to implement in smaller enterprises. Despite it being generally accepted that small enterprises with less than 50 employees have higher exposure to occupational hazards than larger organisations, smaller enterprises often have limited resources to prioritise risks and to improve the working environment, and they often have difficulties in complying with legislation.

Low Back pain (LBP) is a common health problem. Furthermore, long-term back pain often exerts a negative impact on participation in everyday activities. Health professionals strongly emphasise the importance of focusing rehabilitation on aspects that improve the patient’s well-being and quality of life. Return To Work (RTW) might then be a possible, but not a necessary, feature of LBP rehabilitation. This is one explanation for the modest effect rehabilitation has exerted on reduced sickness absence.

Low Back pain (LBP) is a common health problem. Furthermore, long-term back pain often exerts a negative impact on participation in everyday activities. Health professionals strongly emphasise the importance of focusing rehabilitation on aspects that improve the patient’s well-being and quality of life. Return To Work (RTW) might then be a possible, but not a necessary, feature of LBP rehabilitation. This is one explanation for the modest effect rehabilitation has exerted on reduced sickness absence.